Discovery, Renaissance and Reformation, 1500-1650

The Age of Exploration, ~1450 to 1600

The onset and progress of “discovering” the new world is a subject that could fill an entire website by itself. Briefly, the view of the Catholic Western world during the Middle Ages was expressed by Pope Urban II at the beginning of the Crusades in 1095 in his Papal Bull Terra Nullius – a decree explaining the policy of the Catholic Church about empty land. This decree gave European kings the right to “discover” and claim land in non-Christian areas. In 1452, Pope Nicholas V extended this policy through the Papal Bill Romanus Pontifex that authorized the conquest of non-Christian nations and territories.

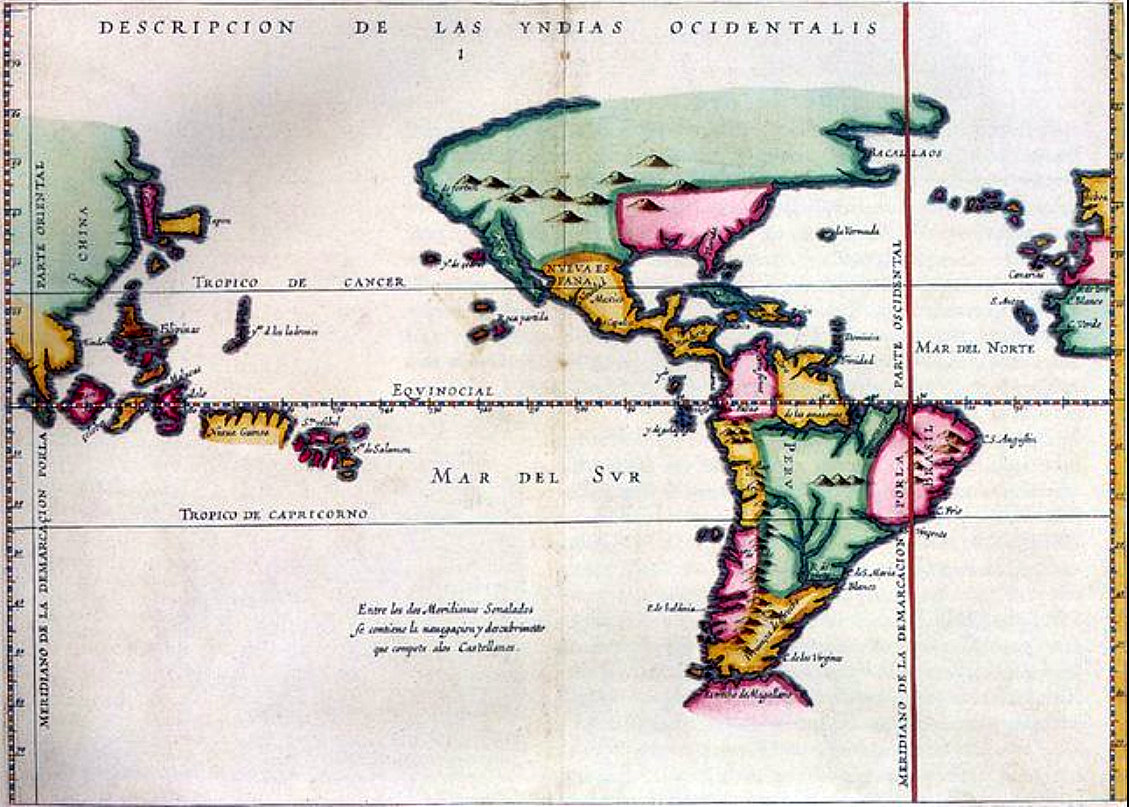

Starting in the early 15th Century, Portuguese seamen progressively began to explore the northern coast of Africa which led to navigation around the western coast and beyond. Inspired by these findings and a growing awareness that the earth was round, Spain commissioned Christopher Columbus to sail west across the Atlantic ocean in search of a new trade route to Asia. When controversy broke out between the two nations, the Spanish Pope Alexander VI issued another Papal Bull in 1493, “granting” to Spain the right to conquer the lands which Columbus had already found, as well as any lands which Spain might “discover” in the future. This led to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas in which Spain and Portugal agreed to “lines of demarcation” dividing America from Europe on the east and from Asia on the west. Thus began centuries of Western colonialism and imperialism.

The 1622 map above depicting the extent of Spanish possessions in America was part of a multi-volume historical work by Herrera, Spain’s official historian. The work relates events of discovery, pacification, and settlement by Spaniards in America between 1492 and 1555. Herrera availed himself of all the documents in the possession of the crown and the Council of the Indies, using them so extensively that for almost two centuries his work constituted an easy means of access to numerous unpublished documents and manuscripts.

Page background image – Universalis Cosmographia, completed in 1507 by Martin Waldseemuller, this is the first known map in which the New World is named America.

The High Renaissance

The Renaissance, which began in Italy in the 14th century with a passionately renewed interest in classical philosophy, literature, and the arts and sciences, spread throughout Europe and beyond and reached its full blossoming in the “High Renaissance” of the 16th century.

During this time explorers, primarily from Spain and Portugal as noted above, reached both east and west from Europe to chart the world and fill it with commerce.

Remarkably talented Renaissance men and women like Raphael, Leonardo DaVinci, Michelangelo, Isabella d’Este, Sandro Botticelli. Donatello, Galileo, and Copernicus expanded the boundaries of knowledge, art, literature, and the sciences.

Historical political figures from this period included Lorenzo de’ Medici (father of Pope Leo X), Niccolò Machiavelli, and Thomas More.

A detail taken from the center of Raphael’s huge fresco “The School of Athens” depicting Plato and Aristotle surrounded by other classical luminaries of philosophy. Painted in 1509-1511, it is one of several he was commissioned to paint in the Palace of the Vatican (papal apartments) and has long been seen as “Raphael’s masterpiece and the perfect embodiment of the classical spirit of the Renaissance”. Click on the image to open a picture of the entire painting that identifies the main personages. For a remarkable overview of the position of the Church of Rome during the High Renaissance, visit the Raphael Rooms to see and read about the other frescoes Raphael and his studio were commissioned to paint in the Palace. Click on image for details and identification of characters.

The Condition of the Church

The Church in Rome was in its peak of power, wealth, corruption, and worldly glory. Teachings of classical scholars like Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates were being syncretistically incorporated into those of the Roman Church, and a new way of dealing with guilt and sin was promoted: papal Indulgences. With humanism and its glorification of the mind and body of man on full display, centuries-old guidelines of moral behavior in Christendom had become more and more relaxed, and licentiousness was beginning to run rampant especially among the wealthy and powerful, not to the exclusion of church leaders.

There is a price to be paid for sin, but instead of turning from sin in conviction and repentance and receiving Christ’s forgiveness and sacrifice in payment, people were taught that they could pay money to the Church in Rome and receive an official pardon (“Indulgence”) from the Pope, along with a promise that the punishment for their sins would be ameliorated. Much of the money collected was used to build or rebuild magnificent Renaissance structures in Rome like St. Peter’s Basilica, expand and decorate the Vatican Palace and Sistine Chapel with their world-famous works of art, and pay the debts of Leo X (Pope from 1513-1521), who became best known for his extravagant benefices, wasteful habits, lecherous activities, and hedonistic quote, “Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it.” Three years after Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses in 1517 condemning the Pope’s behavior and practice of selling Indulgences and asking for dialogue, Leo X issued a papal bull to excommunicate him. Leo died later that year, however, before seeing Luther’s Reformation take full hold.

The worldly corruption of the visible Church, which began taking a notable turn in that direction around the time of Constantine and accelerated as the Renaissance progressed, had reached new depths that were not beyond the notice of humanity or the reach of the Most High God.

Luther’s 95 Theses begin Reformation in 1517

In Germany a Dominican friar and preacher, Johann Tetzel, became an aggressive marketer of Indulgences for Pope Leo X and provoked Martin Luther, professor of moral theology at the University of Wittenberg, to write his Ninety-five Theses criticizing what he saw as the purchase and sale of salvation. On October 31, 1517 (the eve of All Saint’s Day) he sent a copy of the Theses to his Archbishop, Albert of Brandenburg, asking for an academic discussion of the matter. In Thesis 28 Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel: “As soon as a coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs”. The Ninety-five Theses not only denounced such transactions as worldly but denied the Pope’s right to grant pardons on God’s behalf in the first place: the only thing indulgences guaranteed, Luther said, was an increase in profit and greed because the pardon of the Church was in God’s power alone. The timeline of the Reformation had begun.

The Reformation spreads

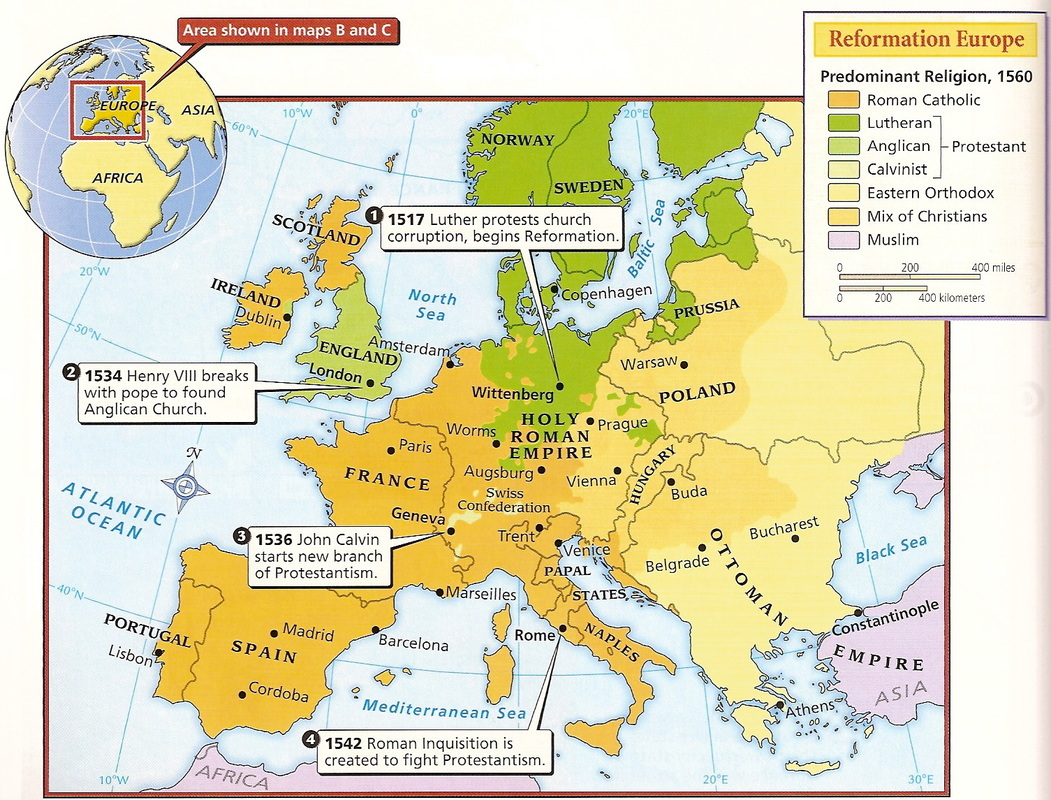

Facilitated by Gutenberg’s press and fueled by frustration, anger at the Church, new vistas opening up, and hopefully in significant measure by the guiding presence of the Holy Spirit, the truths uncovered in the Reformation rapidly spread throughout Europe. Click on the accompanying map showing the state of affairs in 1560, only 40 brief years after Luther’s Theses were revealed, to study it more closely. John Calvin and other leaders had emerged; Henry VIII in England had separated the Anglican from Rome; and a backlash from Rome had begun. The transitions that took place were often far from peaceful.

The Reformation has properly been called the “Protestant Reformation” because it originated a clearly defined “protest” against the behavior of the Roman Church and its leaders, and sought to “reform” that Church, not replace or supersede it. Unfortunately, the attempts of Luther and others to dialogue with the Pope and hierarchy were not constructively received, and the Church was splintered.

The Reformation Continues

Both in the process of trying to work things out within the Roman Church and after the break, Luther applied his gifts in prayer, intercession, scholarship, preaching, and writing to the task of documenting (ultimately in 55 volumes!) and disseminating what he perceived were the “Five Solas” or truths of the Gospel and the proper calling and discipleship of a faithful Ekklesia of converted Christians. As we can see in the map above, others rapidly began to pick up the same work. The sad fact was that the Roman Church had become so far removed from the original expression of the faith Jesus had lived, proclaimed so clearly, and died to reveal that the awareness struck a chord with countless people. Unfortunately, human beings are limited personally and by the culture in which they live, and the result became confusing with sincere advocates moving in various directions either simultaneously or sequentially carrying the mixture of truth and tradition that they had received. In the midst of this, the faith that had become unified as a system in Christendom became fragmented into a variety of different “denominations” (a word which means “under the name”).

Notable Early Leaders in the Reformation Movement

1. Leaders prior to Luther’s time included 14th century reformers like John Wycliffe (1320s-1384) at Oxford University and Jan Hus (1369-1415) at the Charles University in Prague. Both of these men were passionate and articulate Christian scholars who extensively critiqued perceived errors in Catholic theology and administrative practice and attracted many adherents in their homelands of England and Bohemia/Moravia (modern Czech Republic) before being condemned as heretics and burned.

2. Magisterial Reformers (argued for the interdependence of the church and secular authorities) included Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) and John Calvin (c. 1505-1572).

Zwingli was an ordained Catholic priest and humanist scholar in Switzerland who was appointed to the pastorate in Zürich in 1518, one year after Luther posted his Theses. Soon after arriving, Zwingli’s preaching began to depart from the traditional Roman model, elaborating instead on interpretive teachings from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s humanist version of the New Testament. In 1520 he began to preach pointed sermons on the moral corruption he saw in the Roman Church, and by 1522 he was openly challenging parts of Roman doctrine, which caused quite a stir in Zürich. After two public “disputations” concerning the elimination of icons from churches and relaxing requirements for the celebration of the mass, Zwingli became more and more influential. He felt that the cornerstone of Christian witness and theology should be the Bible, read with an understanding of Reformed theology and interpreted from a rationalistic humanist perspective in contrast to literalist interpretations such as those of the Anabaptists. Zwingli’s legacy is embodied in his commitment to the Bible, advocacy for the poor, sense of humor, love of music, and desire to see God glorified through compassionate government.

John Calvin was a French lawyer who broke from the Roman Church in 1530 and became part of the Protestant movement in France. When persecution of Protestants became severe there, he fled to Switzerland where he began writing and continuously expanding his magnum opus called “Institutes of Christian Religion”, which was an extensive Protestant system of theology that became known as Calvinism. He joined other magisterial reformers in Geneva where he preached regularly and served for many years as an apologist, reformer, theologian, and pastor, sometimes in the midst of strife and opposition. He eventually became the undisputed leader of Geneva and founded a college which became the University of Geneva. Calvin’s followers included John Knox in Scotland (c. 1505-1572), and many Congregational, Reformed and Presbyterian churches trace their foundational beliefs to those so clearly expounded in his teachings.

The changes that took place in England during the early to mid 16th century during and following the notorious reign of Henry VIII perhaps fall into this category with some qualification, since the separation of the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church was motivated more out of Henry VIII’s immoral desires to be united sexually and in marriage with a sequence of women. Nonetheless, the result was that the Church in England became Protestant in governance and to a progressive degree in doctrine as the years went by, with the initial “protest” having more to do with rebellion than reform. We will take up the subsequent Puritan reform movement in England and Huguenots in France in our next page on the New World and Enlightenment.

3. Radical Reformers who also first arose in Germany and Switzerland, were numerous and diverse in their protest against the corruption they saw in the Roman Church. Rather than seeking to reform the Roman Church, which they saw as inextricably entangled in the ways and power of the world, they sought to see the Christian Church (ekklesia) reborn as a separate kingdom from those of the world. This group included Andreas Karlstadt (excommunicated along with Luther), Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525), the Zwickau prophets, and Anabaptists like the Mennonites and Hutterites. Although the Radical Reformers were diverse, they shared common views of the faith, many of which were documented in the Schleitheim Confession of 1527. These included freedom of the will, salvation by Divine grace, believers’ (or adult) baptism, discipleship leading to ethical living, the Lord’s Supper as a memorial not a sacrifice, Scripture as the final authority on matters of faith and practice with an emphasis on the New Testament and the Sermon on the Mount, the need to interpret Scripture in community, separation from the world and a two-kingdom theology, pacifism and nonresistance, communalism and economic sharing, “yieldedness” to one’s community and to God, non-swearing of oaths, and excommunication.

4. The Catholic Reformation (also known as the Counter-Reformation) was a process that started shortly after the Protestant Reformation was underway, once it became clear that the Protestant reformers had addressed some serious and real problems in the Roman Church and that Protestantism was spreading rapidly with no signs of going away. The efforts of the Catholic reformers were directed not only at church politics and policy, but also included major figures such as Ignatius of Loyola, Teresa of Ávila, John of the Cross, Francis de Sales, and Philip Neri, who added to the spirituality of the Catholic Church. Major reforms in art and church music took place, as well, many of which were accomplished during the Council of Trent held between 1545 and 1563.

Atlantic Slave Trade

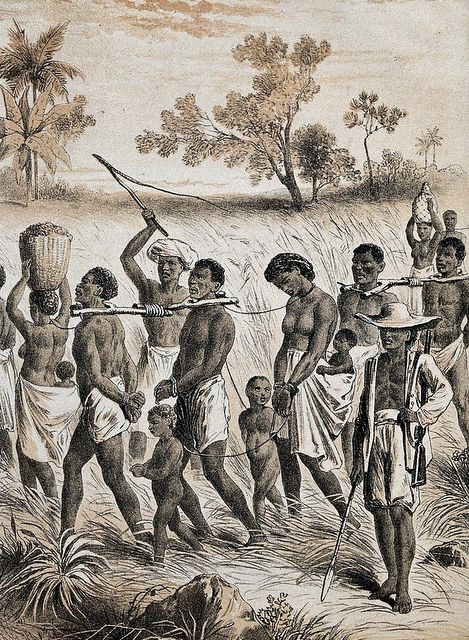

Slavery had been well-established in many parts of Africa for centuries prior to the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade with captives from some parts of Africa being exported to other parts of Africa as well as places in Europe and Asia, well before the Americas were discovered and colonized by European nations. When navigation on the Atlantic became well-known in the 16th century, literally hundreds of commercially motivated explorers carrying colonists and material plied the ocean waters, allowing settlers to take over vast portions of land from the native peoples living along Africa’s western coast and in the newly discovered Americas and turn them to agriculture and commerce. As European nations built up economically slave-dependent colonies in the New World, African slave traders took advantage of the situation, many of whom had become adept at rounding up indigenous prisoners of war from the tribal conflicts that were endemic to Africa (often inflamed by the traders themselves) and selling them on the newly expanded west African and American colonial markets. British, Portuguese and French were the main carriers.

This was the beginning of one of history’s deepest and most pervasive moral, social, political, and cultural blights, the after-effects of which continue to plague us to this day, over 150 years after the abolition of the institution of slavery.

Later Reformation – Pilgrims and Puritans

Standing at the juncture of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment at the turn of the 17th century were some of Europe’s most committed reformers, men and women of vital faith who challenged the orthodoxy of the established liturgical churches of their day with freshly rediscovered truths from both Old and New Testament writers. The Renaissance had looked back to rediscover truths that may have been lost from civilization’s human glories in Greece prior to the time of Christ, while the Enlightenment sought to discover new truths in science and reason. In the midst of this, the reformers straddled the influences of their age by seeking to have the eternal truths in Scriptures, which had been long sequestered in Latin and doctrine by the Church, illuminated by inspiration and reason. The Gutenberg press had spawned a proliferation of published material about Reformation ideas, including translations of the Bible into native tongues like the widely acclaimed King James Version published in England in 1611, and the Reformation spread throughout the nations, further fragmenting the once powerful and unified control the Roman Church had held in matters of faith.

For example, in 1534 during the height of the early Reformation in England, Henry VIII had wrested control of the Church from Rome for rather specious and self-serving reasons: he wanted to divorce his wife and marry a mistress. The result was the Church of England, now known as the Anglican Church (or the Episcopal Church in America after 1776). However, little reformation other than changes in authority structure from Pope to King had taken place. In the following decades interest in theological developments began to take hold, however, kindled when the spiritually lively teachings of Luther, Calvin, Knox, and other reformers began revealing the treasures of Heaven available through faith (trust) in the finished work of the Savior rather than through the Sacraments of the Church alone. A revival of saving faith came to England, and many earnestly converted men and women sought to see their national Church come alive with the newly discovered truths of genuine faith. Unfortunately, their earnestness was often met with persecution.

There were two manifestations of the Reformation, those who thought the established Church could be reformed and those who deemed it to be irretrievably apostate. Both were persecuted. In England the latter group included the Pilgrims who began colonizing northern America when they landed in Plymouth harbor in 1620. The former were the Puritans who followed the Pilgrims to the New World in waves during the following decades, establishing communities of dedicated Christian believers throughout what became known as New England. During the same time period colonies of brave Englishmen seeking a new life were developed in Jamestown and the area surrounding what is now Virginia, sponsored by the King and carrying the institution of the Church of England to the New World. Sadly, the institution of slavery was carried along with colonization, both north and south.

Navigation Notes

Look below and notice the Up and Down buttons in the middle. Using these buttons you can navigate directly through our timelines. For each timeline we will take a detailed tour using the outside buttons to investigate historical events and people noted on the current chart. Our current Chart 7 tour has brought us so far through the Birth of the Church, early spread of the Gospel, and the establishment and expansion of the visible Church in the centuries leading up and through the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and early Reformation. Our next stop will cover the period of the Enlightenment from the early 1600s up to 1800 AD.