The “Enlightenment” or “Age of Reason” – 1650 to 1800+

An outgrowth of Renaissance Humanism

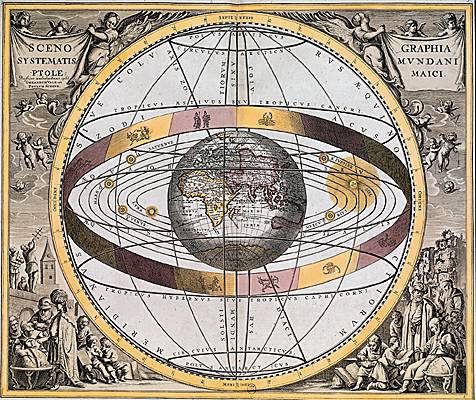

The 17th Century emerged during a time of dramatic change in the worldview of Western Civilization from one in which established Church doctrine was being challenged with Biblical insights from within and non-Biblical Islamic expansionism from without, to a more worldly outlook stimulated by dramatic advances in exploration, mathematics, physics, science, economics, and political scholarship. Advanced communication, urbanization, social mobility, expanding education, and yearning for freedom and democratic forms of governance were key elements at work during the period.

Man was beginning to experience the powers of his intellect, and a proud form of humanism was emerging from the Renaissance which felt more and more free to explore the past, present, and future with less and less reference to Biblical faith or even God. While the Reformation surged onward throughout Europe and into America, the confusion and strife its advance had left in its wake left many disillusioned with matters of faith and more open to building their lives on the hope of human development and progress apart from God. Instead of looking to religion and the past for inspiration, men were looking within and to the future for hope.

Scholarly Advances in the Arts and Sciences

Several seminal personalities, first in France and later in England and other parts of Europe, as well as daring new discoveries and ideas came to the forefront in the 17th Century which, together, began to captivate the imagination of Western Civilization:

René Descartes (1596-1650), a French mathematical genius and Renaissance man with deep insights into philosophy and science, was perhaps the most influential scholar to expound the man-centered rationalist philosophy (“I think, therefore I am”) that became the foundation for the enlightenment worldview. It is interesting to note that much of his passion and motivation to search the limits of human understanding emerged after he experienced three unusual dreams during the night of November 11, 1619 which led him to believe that a divine spirit had revealed a new metaphysical philosophy to him. He went on to study, write, and develop a dualistic doctrine of mind and matter which led him to question every area of study until he felt he had arrived at a rational explanation, thus shifting the prevailing quest for knowledge from the dominant “what is true” to the new “of what can I be certain?” His approach was adopted by John Locke , expanded upon by David Hume later, and widely adopted. Although Descartes believed in a rational God and remained a nominal Catholic throughout his life, his philosophy clearly separated the subjective action of the human mind from the workings of God, and his writings were placed on a list of “prohibited books” by the Pope in 1666,

Voltaire (1694-1778), an acerbic and prolific French writer, philosopher, and social critic, became one of the principal spokespersons for the Enlightenment values of individual civil liberty, separation of church and state, and freedom of speech and religion. His works were noteworthy for their controversial content, harsh criticism of the Church, dogma, and the established institutions of France. Although much acclaimed as an author and playwright, Voltaire had a number of encounters with the law, was exiled to England briefly, carried on an open affair with a younger married philosopher for nearly two decades, and then moved to Prussia. A confirmed but dispassionate Deist, he died shortly after his return to France in 1778, apparently without repenting from the vilification he had heaped upon Christianity and Judaism throughout his life.

Rousseau (1712-1778), a somewhat gentler and more nuanced French Enlightenment philosopher than Voltaire, was noted for his musical compositions and the political philosophy he outlined in his major work The Social Contract. Although he became a committed Calvinist during his later years in Geneva, his philosophy more resembles an emotionally engaged form of deism than orthodox Christian faith.

Other Enlightenment influencers included Montesquieu (also French), Cesare Beccaria in Italy, Immanuel Kant in Germany, and John Locke and Mary Wollstonecraft in England, as well as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin in America.

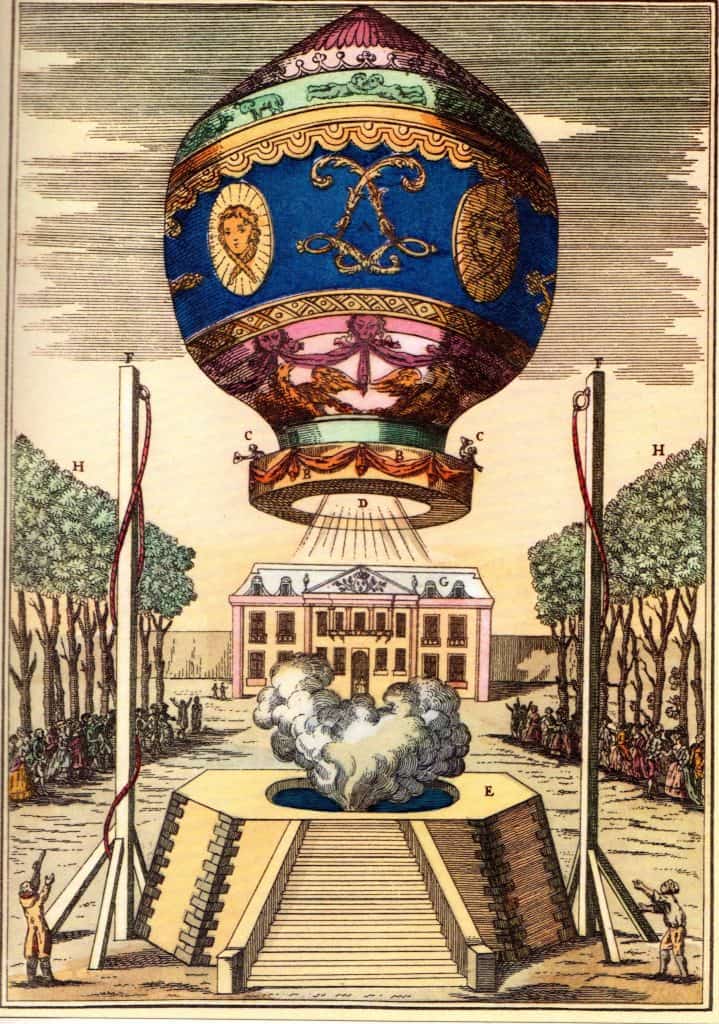

Most advances in science developed in the latter half of the 18th Century in chemistry (Antoine Lavoisier), physics (Isaac Newton), and the applied sciences of which the most well-known was James Watts’ invention of the condensing steam engine and the Montgolfier Brothers‘ experiments that led to their ascent in a hot air balloon.

The Montgolfier Hot Air Balloon, 1783

Going for Baroque

The Baroque period in the European art and music world , characterized by strict musical forms and highly ornamental works, began right around the end of the Renaissance in 1600 and merged into the Classical period a century later. Operatic, chamber, and orchestral music flourished throughout Western civilization.

In 1666 Stradivarius opened his famous violin shop and produced masterpieces that remain with us to this day. Some of the noteworthy musicians and composers during this musical time period that remain well-known today include Monteverdi in Italy, followed later by Bach, Purcell, Vivaldi, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven. Famous painters from this period include Caravaggio, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin, and Vermeer.

Key Enlightenment Ideas and Beliefs

Although Enlightenment philosophers and luminaries (if we may use that term) presented a veritable smorgasbord of ideas about human “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” of which there are five (all derived from the first, the “light” that supposedly comes from unfettered human reason) that may serve to summarize the intellectual and social movement that resulted, a movement which is very active to this very day:

- Reason: The power of human reason alone (homo solus) can explain the world and lead to right and moral answers in the absence of any active participation of God in the affairs of mankind. Belief in God is optional at best and destructive at worst.

- Nature: The natural world is ordered according to natural laws established by a rational but distant Creator or by some seemingly rational creative process. Anything natural is deemed to be intrinsically good, true, and reasonable. Inclusion, diversity, and toleration.

- Rights: Individuals have “natural rights,” including the right to self-governance and the freedom from legal constraint to pursue happiness in any way that can be naturally justified. Church and State should be separate. Equality and liberalism.

- Discovery: Combining observation and scientific experimentation with rational thought is the best way to find out what is real and practical. Supernatural revelation is an outmoded myth and tradition a flawed guide. Learning by trial and error.

- Progress: The continuous progressive improvement of society can be expected through the natural application of human reason in the absence of coercion, religious dogma, and superstition. New is intrinsically better than old.

Early American Colonies

While religious unrest and Enlightenment thinking were stirring through Europe, something somewhat different was happening in the growing American colonies across the Atlantic. In marked distinction from the early explorers of the New World, especially those in South and Central America, who had primarily been motivated by the mercantile and Catholic imperial ends of their Portuguese and Spanish sponsors, those who came to the more north central Atlantic shores of America from Jamestown to Plymouth were primarily motivated by religious ideals.

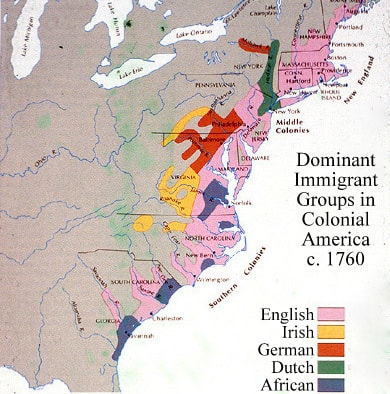

The heritage that Americans have owned for centuries traces back to born-again Protestant Pilgrims and Puritans who emigrated (over 70,000 in the 1630s alone) to escape religious persecution in Europe and establish a new, hopefully more godly society in the New World based on their faith. Down the coast in Jamestown an English settlement of confessed members of the traditional Anglican Church was established. Afterwards similar Irish, German, and Dutch colonists came. Sadly, the first African slaves were brought in 1619.

The Spread of Colonialism

In the beginning, Portugal and Spain (see previous page), inspired by commercial zeal, were primarily interested in overseas trade to the Americas and Philippines. With few exceptions, they managed to avoid developing significant colonial populations.

By contrast, as competition heated up in the 17th century the English, French and Dutch pressed forward and established colonies, initially in neighboring regions along the North American Atlantic coast between the French possessions in modern Canada and the Spanish claims in the South.

As time and exploration advanced, the early imperial empires lost their cohesion. The British won against their French rival in North America and India, against the Dutch in Southeast Asia and against the Spanish in South America. Although the U.S. gained independence from England, British supremacy was maintained in India, South Africa, and especially on the seas with the almost peerless Royal Navy and modern free trade.

Kingdom Insights

Kingdom Insights

The Problem

The effect of Enlightenment thinking was more pronounced in Europe than it was in the American Colonies. However, by the end of the 18th Century there were several prominent leaders in America who identified with the Enlightenment, most notably Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin. Enlightenment Deism, which confessed belief in an absent creator God who was not active in the affairs of man, permeated their worldview and many of the founding documents of our nation, especially the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson even produced an edited version of the Bible with all references to the miracles of Jesus or the divinity of Christ removed.

God’s Response

How did the God of the universe respond to this challenge? Gently, patiently, and with a plan that can be discerned more clearly in retrospect. He allowed His more devoted followers to be persecuted in Europe, then guided them in huge numbers to the shores of the New World where He helped them set up a society in America that was open to carrying the Gospel (“good news”) message to the world. Then, when their insight and commitment began to wane, He poured out His Spirit and brought waves of Awakening.

“The LORD has established His throne in the heavens, and His kingdom rules over all.” Psalm 103:19

A Reawakening of Christian Faith

As noted, a large majority of the founding immigrants who formed colonial America in the 17th Century were people motivated by an awakened personal Christian faith. As time passed and populations and commerce increased causing communities to form up and down the Atlantic seaboard, the unity of their faith became somewhat diluted with world divisions and concerns. Participation in church gatherings diminished, and the convictions of the early colonists failed to carry over into subsequent generations with the same fervor. In Europe, Enlightenment thinking had become more and more dominant and was now beginning to suffuse into American culture.

In the early 18th Century a strong current of revival started in New England and began to spread throughout the Colonies leading to what came to be known as “The Great Awakening.” Under the spiritual influence mediated by passionate and persuasive preachers like Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and many others, multitudes of colonists became aware of and began to confess and turn away from their keenly perceived lack of gratitude and spiritual failings. The ranks of churches swelled, alcoholism and domestic strife subsided, and communities rose to higher levels of piety, peace, and harmony. The events and activities of the Great Awakening became so visible that they spread back across the Atlantic and began to effect similar changes among Lutherans and Reformed Church members on the Continent as well as stimulating a similar Evangelical Revival in Scotland and England with the Wesley brothers (Anglican founders of what became Methodism) and many others.

Navigation Notes

Look below and you’ll notice Up and Down buttons in the middle. Using these buttons you can navigate directly through our timelines. For each timeline we will take a detailed tour using the outside buttons to investigate historical events and people noted on the current chart (the preferred route, especially for your early visits to our website). Our Chart 7 tour is allowing us to look more closely at the spread of the Gospel and the establishment, expansion, and various movements in the Church in the centuries leading up to Modern times. Our next stop will be in the Late Modern period from 1800-1960, almost to where we’re living now.