Terminology

Author’s Note: The subject material covered in this website is extensive and often uses specialized words and discusses concepts and subjects that have been studied extensively and developed very particular meanings. In the course of my studies I’ve collected and listed a number of these below, along with excerpted definitions I’ve drawn from dictionaries, scholarly articles, and Wikipedia for your consideration. Many of these have been referenced in the pages of this website, often with links. If you have a question about a word or concept that you encounter along the way, check here to see if I’ve included it in our list. Just reading through the definitions below will give you a good idea of the scope of the material being addressed in the pages of HisKingdom.Us.

Ages or Æons

The word aeon /ˈiːɒn/, also spelled eon (in American English) and æon, originally meant “life”, “vital force” or “being”, “generation” or “a period of time”, though it tended to be translated as “age” in the sense of “ages”, “forever”, “timeless” or “for eternity”. It is a Latin transliteration from the koine Greek word ὁ αἰών (ho aion), from the archaic αἰϝών (aiwon). In Homer it typically refers to life or lifespan. Its latest meaning is more or less similar to the Sanskrit word kalpa and Hebrew word olam. A cognate Latin word aevum or aeuum (cf. αἰϝών) for “age” is present in words such as longevity and mediaeval.

Although the term aeon may be used in reference to a period of a billion years (especially in geology, cosmology or astronomy), its more common usage is for any long, indefinite, period.

The Bible translation is a treatment of the Hebrew word olam and the Greek word aion. These words have similar meaning, and Young’s Literal Translation renders them and their derivatives as “age” or “age-during”. Other English versions most often translate them to indicate eternity, being translated as eternal, everlasting, forever, etc. However, there are notable exceptions to this in all major translations, such as Matthew 28:20: “…I am with you always, to the end of the age” (NRSV), the word “age” being a translation of aion. Rendering aion to indicate eternality in this verse would result in the contradictory phrase “end of eternity”, so the question arises whether it should ever be so. Proponents of universal reconciliation point out that this has significant implications for the problem of hell. Contrast Matthew 25:46 in well-known English translations with its rendering in Young’s Literal Translation:

- And these shall go away to punishment age-during, but the righteous to life age-during. (YLT)

- Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life. (NIV)

- These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life. (NASB)

- And these shall go away into everlasting punishment, but the righteous into eternal life. (KJV)

- And these will depart into everlasting cutting-off, but the righteous ones into everlasting life. (NWT)

The Ages of Man are the stages of human existence on the Earth according to Greek mythology and its subsequent Roman interpretation. Both Hesiod and Ovid offered accounts of the successive ages of humanity, which tend to progress from an original, long-gone age in which humans enjoyed a nearly divine existence to the current age of the writer, in which humans are beset by innumerable pains and evils. In the two accounts that survive from ancient Greece and Rome, this degradation of the human condition over time is indicated symbolically with metals of successively decreasing value.

Agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown and unknowable. An agnostic can also be one who holds neither of two opposing positions on a topic.

The English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the word agnostic in 1869, and said “It simply means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe.” Earlier thinkers, however, had written works that promoted agnostic points of view, such as Sanjaya Belatthaputta, a 5th-century BCE Indian philosopher who expressed agnosticism about any afterlife; and Protagoras, a 5th-century BCE Greek philosopher who expressed agnosticism about the existence of “the gods”. The Nasadiya Sukta in the Rigveda is agnostic about the origin of the universe.

According to the philosopher William L. Rowe, “agnosticism is the view that human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that God exists or the belief that God does not exist”.

Agnosticism is the doctrine or tenet of agnostics with regard to the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena or to knowledge of a First Cause or God, and is not a religion.

Ancient of Days

Ancient of Days is a name for God in the Book of Daniel: in the original Aramaic atik yomin עַתִּיק יֹומִין; in the Septuagint palaios hemeron (παλαιὸς ἡμερῶν); and in the Vulgate antiquus dierum. The title “Ancient of Days” has been used as a source of inspiration in art and music, denoting the creator’s aspects of eternity combined with perfection. William Blake’s watercolor and relief etching entitled The Ancient of Days is one such example.

The term appears three times in the Book of Daniel (7:9, 13, 22), and is used in the sense of God being eternal: “I beheld till the thrones were cast down, and the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire.” — Daniel 7:9

In Eastern Orthodox Christian hymns and icons, the Ancient of Days is sometimes identified with God the Father or occasionally the Holy Spirit; but most properly, in accordance with Orthodox theology he is identified with God the Son, or Jesus. Most of the eastern church fathers who comment on the passage in Daniel (7:9-10, 13-14) interpreted the elderly figure as a prophetic revelation of the son before his physical incarnation. As such, Eastern Christian art will sometimes portray Jesus Christ as an old man, the Ancient of Days, to show symbolically that he existed from all eternity, and sometimes as a young man, or wise baby, to portray him as he was incarnate. This iconography emerged in the 6th century, mostly in the Eastern Empire with elderly images, although usually not properly or specifically identified as “the Ancient of Days.” The first images of the Ancient of Days, so named with an inscription, were developed by iconographers in different manuscripts, the earliest of which are dated to the 11th century. The images in these manuscripts included the inscription “Jesus Christ, Ancient of Days,” confirming that this was a way to identify Christ as pre-eternal with the God the Father. Indeed, later, it was declared by the Russian Orthodox Church at the Great Synod of Moscow in 1667 that the Ancient of Days was the Son and not the Father.

In the Western Church similar figures usually represent only God the Father. Building his argument upon the Daniel passage, Thomas Aquinas recalls that some bring forward the objection that the Ancient of Days matches the Person of the Father, without necessarily agreeing with this statement himself.

In the hymn “Immortal, Invisible, God only Wise”, the last two lines of the first verse read: Most blessed, most glorious, the Ancient of Days, Almighty, victorious, Thy great Name we praise.

Daniel 7:13-14 says, “I kept on beholding in the visions of the night, and, see there! with the clouds of the heavens someone like a son of man happened to be coming; and to the Ancient of Days he gained access, and they brought him up close even before that One. And to him there were given rulership and dignity and kingdom, that the peoples, national groups and languages should all serve even him. His rulership is an indefinitely lasting rulership that will not pass away, and his kingdom one that will not be brought to ruin.” From a Christian perspective, this may be understood to be describing the Ancient of Days [God the Father] bestowing rulership upon the Son of Man [God the Son, Jesus] , a separate entity. Among ancient Christian pseudepigrapha, one Book of Enoch states that he who is called “Son of man,” who existed before the worlds were, is seen by Enoch in company with the “Ancient of Days.”

- [Note that “rulership” in the last paragraph above is Biblically synonymous with “kingdom“.]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_of_Days

Apocalypse

Ancient Greek: ἀποκάλυψις apokálypsis, from ἀπό and καλύπτω, literally meaning “an uncovering”]

An apocalypse is a disclosure of knowledge or revelation. Historically, the term has a heavy religious connotation as commonly seen in the prophetic revelations of eschatology and were obtained through dreams or spiritual visions.

It is also the Greek word for the last book of the New Testament entitled “Revelation”. The term is also included in the title of some non-biblical canon books involving revelations. Today, the term is commonly used in reference to any larger-scale catastrophic event, or chain of detrimental events to humanity or nature. In all contexts, the revealed events usually entail some form of an end time scenario or the end of the world or revelations into divine, heavenly, or spiritual realms.

Apocalyptic is from the word apocalypse, referring to the end of the world. Apocalyptic literature is a genre of religious writing centered on visions of the end of time.

- In particular, the Book of Revelation (also called the Apocalypse of John) in the New Testament

- Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction, science fiction or horror fiction involving global catastrophic risk

- Apocalypticism, the belief that the end of time is near

Atheism

Atheism is, in the broadest sense, the absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is the rejection of belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities. Atheism is contrasted with theism, which, in its most general form, is the belief that at least one deity exists.

The etymological root for the word atheism originated before the 5th century BCE from the ancient Greek ἄθεος (atheos), meaning “without god(s)”. In antiquity it had multiple uses as a pejorative term applied to those thought to reject the gods worshiped by the larger society, those who were forsaken by the gods, or those who had no commitment to belief in the gods. The term denoted a social category created by orthodox religionists into which those who did not share their religious beliefs were placed. The actual term atheism emerged first in the 16th century. With the spread of freethought, skeptical inquiry, and subsequent increase in criticism of religion, application of the term narrowed in scope. The first individuals to identify themselves using the word atheist lived in the 18th century during the Age of Enlightenment. The French Revolution, noted for its “unprecedented atheism,” witnessed the first major political movement in history to advocate for the supremacy of human reason. The French Revolution can be described as the first period where atheism became implemented politically.

Arguments for atheism range from the philosophical to social and historical approaches. Rationales for not believing in deities include arguments that there is a lack of empirical evidence, the problem of evil, the argument from inconsistent revelations, the rejection of concepts that cannot be falsified, and the argument from nonbelief. Nonbelievers contend that atheism is a more parsimonious position than theism and that everyone is born without beliefs in deities; therefore, they argue that the burden of proof lies not on the atheist to disprove the existence of gods but on the theist to provide a rationale for theism. Although some atheists have adopted secular philosophies (e.g. secular humanism), there is no one ideology or set of behaviors to which all atheists adhere.

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek τὰ βιβλία, tà biblía, “the books”) is a collection of sacred texts or scriptures. Varying parts of the Bible are considered to be a product of divine inspiration and a record of the relationship between God and humans by Christians, Jews, Samaritans, and Rastafarians.

What is regarded as canonical text differs depending on traditions and groups; a number of Bible canons have evolved, with overlapping and diverging contents. The Hebrew Bible overlaps with the Greek Septuagint and the Christian Old Testament. The Christian New Testament is a collection of writings by early Christians, believed to be mostly Jewish disciples of Christ, written in first-century Koine Greek. Among Christian denominations there is some disagreement about what should be included in the canon, primarily about the Apocrypha, a list of works that are regarded with varying levels of respect.

Attitudes towards the Bible also differ among Christian groups. Roman Catholics, high church Anglicans and Eastern Orthodox Christians stress the harmony and importance of the Bible and sacred tradition, while Protestant churches, including Evangelical Anglicans, focus on the idea of sola scriptura, or scripture alone. This concept arose during the Protestant Reformation, and many denominations today support the use of the Bible as the only source of Christian teaching.

The Bible has been a massive influence on literature and history, especially in the Western World, where the Gutenberg Bible was the first book printed using movable type. According to the March 2007 edition of Time, the Bible “has done more to shape literature, history, entertainment, and culture than any book ever written. Its influence on world history is unparalleled, and shows no signs of abating.” With estimated total sales of over 5 billion copies, it is widely considered to be the most influential and best-selling book of all time. As of the 2000s, it sells approximately 100 million copies annually.

Biblical Hebrew “Day”

Yom (Hebrew: יום) is a Biblical Hebrew word which occurs in the Hebrew Bible (or Old Testament). The Arabic equivalent is “yawm” or “yōm” written as يوم.

Overview: Although yom is commonly rendered as “day” in English translations, the word yom has several literal definitions:

- Period of light (as contrasted with the period of darkness)

- General term for time

- Point of time

- Sunrise to sunset

- Sunset to next sunset

- A year (in the plural; I Sam 27:7; Ex 13:10, etc.)

- Time period of unspecified length.

- A long, but finite span of time – age – epoch – season.

Biblical Hebrew has a limited vocabulary, with fewer words compared to other languages, like English (which has the largest). This means words often have multiple meanings determined by context. Strong’s Lexicon yom is Hebrew #3117 יוֹם. The word Yom‘s root meaning is to be hot as the warm hours of a day.

Thus “yom“, in its context, is sometimes translated as: “time” (Gen 4:3, Is. 30:8); “year” (I Kings 1:1, 2 Chronicles 21:19, Amos 4:4); “age” (Gen 18:11, 24:1 and 47:28; Joshua 23:1 and 23:2); “always” (Deuteronomy 5:29, 6:24 and 14:23, and in 2 Chronicles 18:7); “season” (Genesis 40:4, Joshua 24:7, 2 Chronicles 15:3); epoch or 24-hour day (Genesis 1:5,8,13,19,23,31) – see “Use in creationism” below.

Yom relates to the concept of time. Yom is not just for day, days, but for time in general. How yom is translated depends on the context of its use with other words in the sentence around it, using hermeneutics.

The word day is used somewhat the same way in the English language, examples: “In my grandfather’s day, cars did not go very fast” or “In the day of the dinosaurs there were not many mammals.”

The word Yom is used in the name of various Jewish feast days; as, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement; Yom teruah (lit., day of shouting) the Feast of Trumpets.[13]

Yom is also used in each of the days of the week in the Hebrew calendar.

Use in creationism

- Young Earth creationism Yom has various meanings depending on its context, but the consecutive days in Genesis 1 mean 24 hours.

- Gap creationism Yom is 24 hours, but there are gaps of time.

- Old Earth creationism Yom is time span.

- Day-age creationism Yom is time span.

- Progressive creationism Yom is time span, but there are gaps of time.

- Evolutionary creationism (or Theistic evolution, making theory of evolution and Bible compatible): the literal interpretation of Yom not as crucial.

Christian Church (Ekklesia or Ecclesia)

Ekklesia (from Greek ekklesia [ἐκκλησία] or Ecclesia in Latin) in Christian theology means both a particular body of faithful people and the whole body of the faithful. Ekklesia, had an original meaning of “assembly, congregation, council”, literally a “gathering of those summoned” or “convocation”. In English versions of the Bible this has commonly been translated “Church” and refers to God’s redeemed people, called out from the broader community and gathered together for God’s purposes. See also definition of “Ecclesiology” below.

Note: The following Wikipedia article is about followers of Jesus in general. For the buildings used in Christian worship, see Church (building). For an individual church, see Church (congregation). For discussion of organization and relationships between individual churches, see Christian denomination. For other uses, see Christian Church (disambiguation).

“Christian Church” is an ecclesiological term generally used by Protestants to refer to the whole group of people belonging to Christianity throughout the history of Christianity. In this understanding, “Christian Church” does not refer to a particular Christian denomination but to the body of all believers. Some Christian traditions, however, believe that the term “Christian Church” or “Church” applies only to a specific historic Christian body or institution (e.g., the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, or the Assyrian Church of the East). The Four Marks of the Church first expressed in the Nicene Creed are that the Church is One (a unified Body of Particular Churches in full communion of doctrines and faith with each other), Holy (a sanctified and deified Body), Catholic (Universal and containing the fullness of Truth in itself), and Apostolic (its hierarchy, doctrines, and faith can be traced back to the Apostles).

Thus, the majority of Christians globally (particularly of the apostolic churches listed above, as well as some Anglo-Catholics) consider the Christian Church as a visible and institutional “societas perfecta” enlivened with supernatural grace, while Protestants generally understand the Church to be an invisible reality not identifiable with any specific earthly institution, denomination, or network of affiliated churches. Others equate the Church with particular groups that share certain essential elements of doctrine and practice, though divided on other points of doctrine and government (such as the branch theory as taught by some Anglicans).

Most English translations of the New Testament generally use the word “church” as a translation of the Ancient Greek term “ἐκκλησία” (transliterated as “ekklesia“) found in the original Greek texts, which generally meant an “assembly”. This term appears in two verses of the Gospel of Matthew, 24 verses of the Acts of the Apostles, 58 verses of the Pauline epistles (including the earliest instances of its use in relation to a Christian body), two verses of the Letter to the Hebrews, one verse of the Epistle of James, three verses of the Third Epistle of John, and 19 verses of the Book of Revelation. In total, ἐκκλησία appears in the New Testament text 114 times, although not every instance is a technical reference to the church.

In the New Testament, the term ἐκκλησία is used for local communities as well as in a universal sense to mean all believers. Traditionally, only orthodox believers are considered part of the true church, but convictions of what is orthodox have long varied, as many churches (not only the ones officially using the term “Orthodox” in their names) consider themselves to be orthodox and other Christians to be heterodox.

Catholic Church’s definition:

The Catholic Catechism says: “The Church is the Body of Christ. Through the Spirit and his action in the sacraments, above all the Eucharist, Christ, who once was dead and is now risen, establishes the community of believers as his own Body. In the unity of this Body, there is a diversity of members and functions. All members are linked to one another, especially to those who are suffering, to the poor and persecuted. The Church is this Body of which Christ is the head: she lives from him, in him, and for him; he lives with her and in her.”

Etymology:

The Greek term for “church” is ekklesia (found 114 times in the New Testament). For years gospel preachers have called attention to the etymology of ekklesia. The word is a compound of two segments: ek, a preposition meaning “out of,” and a verb, kaleo, signifying “to call” — hence, “to call out.” In the New Testament context, the word is employed in four senses:

1) It represents the body of Christ worldwide, over which the Lord functions as head (Matthew 16:18; Ephesians 1:22; 1 Timothy 3:15).

2) The expression can refer to God’s people in a given region (Acts 9:31, ASV, ESV).

3) Frequently, it depicted a local congregation of Christians (1 Corinthinans 1:2; Revelation 1:11).

4) It could also signify a group of the Lord’s people assembled for worship (1 Corinthians 14:34-35).

Choice

[see also Conscience and Free Will]

Choice involves decision making. It can include judging the merits of multiple options and selecting one or more of them. One can make a choice between imagined options (“What would I do if…?”) or between real options followed by the corresponding action. For example, a traveler might choose a route for a journey based on the preference of arriving at a given destination as soon as possible. The preferred (and therefore chosen) route can then follow from information such as the length of each of the possible routes, traffic conditions, etc. The arrival at a choice can include more complex motivators such as cognition, instinct, and feeling.

Simple choices might include what to eat for dinner or what to wear on a Saturday morning – choices that have relatively low-impact on the chooser’s life overall. More complex choices might involve (for example) what candidate to vote for in an election, what profession to pursue, a life partner, etc. – choices based on multiple influences and having larger ramifications.

Freedom of choice is generally cherished, whereas a severely limited or artificially restricted choice can lead to discomfort with choosing, and possibly an unsatisfactory outcome. In contrast, a choice with excessively numerous options may lead to confusion, regret of the alternatives not taken, and indifference in an unstructured existence; and the illusion that choosing an object or a course, necessarily leads to the control of that object or course, can cause psychological problems.

Cosmos

The cosmos (UK: /ˈkɒzmɒs/, US: /-moʊs/) is the universe. Using the word cosmos rather than the word universe implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity; the opposite of chaos. The cosmos, and our understanding of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in cosmology – a very broad discipline covering any scientific, religious, or philosophical contemplation of the cosmos and its nature, or reasons for existing. Religious and philosophical approaches may include in their concepts of the cosmos various spiritual entities or other matters deemed to exist outside our physical universe.

The philosopher Pythagoras first used the term cosmos (Ancient Greek: κόσμος) for the order of the universe. The term became part of modern language in the 19th century when geographer–polymath Alexander von Humboldt resurrected the use of the word from the ancient Greek, assigned it to his five-volume treatise, Kosmos, which influenced modern and somewhat holistic perception of the universe as one interacting entity.

Cosmology is the study of the cosmos, and in its broadest sense covers a variety of very different approaches: scientific, religious and philosophical. All cosmologies have in common an attempt to understand the implicit order within the whole of being. In this way, most religions and philosophical systems have a cosmology.

Physical cosmology is the scientific study of the universe, from the beginning of its physical existence. It includes speculative concepts such as a multiverse, when these are being discussed. In physical cosmology, the term cosmos is often used in a technical way, referring to a particular spacetime continuum within a (postulated) multiverse. Our particular cosmos, the observable universe, is generally capitalized as the Cosmos.

In physical cosmology, the uncapitalized term cosmic signifies a subject with a relationship to the universe, such as ‘cosmic time’ (time since the Big Bang), ‘cosmic rays’ (high energy particles or radiation detected from space), and ‘cosmic microwave background’ (microwave radiation detectable from all directions in space).

Philosophical cosmology is a branch of metaphysics that deals with the nature of the universe, a theory or doctrine describing the natural order of the universe. The basic definition of Cosmology is the science of the origin and development of the universe. In modern astronomy the Big Bang theory is the dominant postulation.

Covenant theology

[also known as covenantalism, federal theology, or Federalism]

Covenant theology is a conceptual overview and interpretive framework for understanding the overall structure of the Bible. It uses the theological concept of a covenant as an organizing principle for Christian theology. The standard form of covenant theology views the history of God’s dealings with mankind, from Creation to Fall to Redemption to Consummation, under the framework of three overarching theological covenants: those of redemption, of works, and of grace.

Covenentalists call these three covenants “theological” because, though not explicitly presented as such in the Bible, they are thought of as theologically implicit, describing and summarizing a wealth of scriptural data. Historical Reformed systems of thought treat classical covenant theology not merely as a point of doctrine or as a central dogma, but as the structure by which the biblical text organizes itself. Methodist hermeneutics traditionally use a variation of this, known as Wesleyan covenant theology, which is consistent with Arminian soteriology.

As a framework for biblical interpretation, covenant theology stands in contrast to dispensationalism in regard to the relationship between the Old Covenant (with national Israel) and the New Covenant (with the house of Israel (Jeremiah 31:31) in Christ’s blood). That such a framework exists appears at least feasible, since from New Testament times the Bible of Israel has been known as the Old Testament (i.e., Covenant; see 2 Cor 3:14 [NRSV], “they [Jews] hear the reading of the old covenant”), in contrast to the Christian addition which has become known as the New Testament (or Covenant). Detractors of covenant theology often refer to it as “supersessionism” (see Supersessionism below) or as “replacement theology”, due to the perception that it teaches that God has abandoned the promises made to the Jews and has replaced the Jews with Christians as his chosen people on the Earth. Covenant theologians deny that God has abandoned his promises to Israel, but see the fulfillment of the promises to Israel in the person and the work of the Messiah, Jesus of Nazareth, who established the church in organic continuity with Israel, not as a separate replacement entity. Many covenant theologians have also seen a distinct future promise of gracious restoration for unregenerate Israel.

Deism

Deism (/ˈdiːɪzəm/ DEE-iz-əm or /ˈdeɪ.ɪzəm/ DAY-iz-əm; derived from Latin “deus” meaning “god”) is a philosophical belief that posits that God exists as an uncaused First Cause ultimately responsible for the creation of the universe, but does not interfere directly with the created world. Equivalently, deism can also be defined as the view which posits God’s existence as the cause of all things, and admits its perfection (and usually the existence of natural law and Providence) but rejects divine revelation or direct intervention of God in the universe by miracles. It also rejects revelation as a source of religious knowledge and asserts that reason and observation of the natural world are sufficient to determine the existence of a single creator or absolute principle of the universe.

Deism gained prominence among intellectuals as a form of the natural theology widespread during the Age of Enlightenment, especially in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. Typically, deists had been raised as Christians and believed in one God, but had become disenchanted with organized religion and orthodox teachings such as the Trinity, Biblical inerrancy, and the supernatural interpretation of events, such as miracles. Included in those influenced by its ideas were leaders of the American and French Revolutions.

Delusion

Classification Psychiatry ICD-10 Code F22. A delusion is a mistaken belief that is held with strong conviction even in the presence of superior evidence to the contrary. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, or some other misleading effects of perception.

Delusions have been found to occur in the context of many pathological states (both general physical and mental) and are of particular diagnostic importance in psychotic disorders including schizophrenia, paraphrenia, manic episodes of bipolar disorder, and psychotic depression.

Dispensationalism

Dispensationalism is a religious interpretive system for the Bible. It considers Biblical history as divided by God into dispensations, defined periods or ages to which God has allotted distinctive administrative principles. According to dispensationalist theology, each age of God’s plan is thus administered in a certain way, and humanity is held responsible as a steward during that time. Dispensationalists’ presuppositions start with the harmony of history as focusing on the glory of God and put God at its center – as opposed to a central focus on humanity and their need for salvation. A dispensational perspective of scripture is evident in some early Jewish circles, as seen in the Dead Sea Scrolls like the Community Rule (1QS). Early Christian fundamentalists embraced the system as a defense of the Bible against religious liberalism and modernism, and dispensationalism became the majority position within Christian fundamentalism.

Each divine dispensation features a cycle:

- God reveals himself and his truth to humanity in a new way.

- Humanity is held responsible to conform to that revelation.

- Humanity rebels and fails the test.

- God judges humanity and introduces a new period of probation under a new administration.

- Ultimately, dispensationalism demonstrates the progress of God’s revelation to humanity and God’s sovereignty through history – a divine grand narrative.

The number of dispensations discerned by theologians within Biblical history vary typically from three to eight. The three- and four-dispensation schemes are often referred to as minimalist, as they include the commonly recognized divisions[further explanation needed] within Biblical history. The typical seven-dispensation scheme is as follows:

- Innocence – Adam under probation prior to the Fall. Ends with expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Some refer to this period as the Adamic period or the dispensation of the Adamic covenant or Adamic law.

- Conscience – From the Fall to the Great Flood. Ends with the worldwide deluge.

- Human Government – After the Great Flood, humanity responsible to enact the death penalty. Ends with the dispersion at the Tower of Babel. Some use the term Noahide law in reference to this period of dispensation.

- Promise – From Abraham to Moses. Ends with the refusal to enter Canaan and the 40 years of unbelief in the wilderness. Some use the terms Abrahamic law or Abrahamic covenant in reference to this period of dispensation.

- Law – From Moses to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Ends with the scattering of Israel in AD70. Some use the term Mosaic law in reference to this period of dispensation.

- Grace – From the cross to the rapture of the church. The rapture is followed by the wrath of God comprising the Great Tribulation. Some use the terms Age of grace or the church age for this dispensation.

- Millennial Kingdom – A 1000 year reign of Christ on earth centered in Jerusalem. Ends with God’s judgment on the final rebellion.

Numerous purposes for this cycle of administrations have been suggested. God is seen to be testing humanity under varying conditions, while vindicating his ways with humanity in originally granting them free will. The dispensations reveal God’s truth in a progressive manner, and are designed to maximize the glory that will accrue to God as he brings history to a climax with a Kingdom administered by Christ, thus vindicating his original plan of administering rule on earth through “human” means. The goal of the dispensations is summarized by Paul the Apostle in Ephesians 1:9-10, “He made known to us the mystery of His will, according to His kind intention which He purposed in Him with a view to an administration suitable to the fullness of the times, that is, the summing up of all things in Christ, things in the heavens and things on the earth”.

One important underlying theological concept for dispensationalism is progressive revelation. Some non-dispensationalists start with progressive revelation in the New Testament and refer this revelation back into the Old Testament, whereas dispensationalists begin with progressive revelation in the Old Testament and read forward in a historical sense. Therefore, there is an emphasis on a gradually developed unity as seen in the entirety of Scripture. Biblical covenants are associated with the dispensations. When these Biblical covenants are compared and contrasted, the result is a historical ordering of different dispensations. Dispensationalism emphasizes the original recipients to whom the different Biblical covenant promises were written. This has resulted in certain fundamental dispensational beliefs, such as a distinction between Israel and the Church.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dispensationalism

- https://hiskingdom.us/kingdom-bc/pattern/dispensations/

Dominion theology

(also known as dominionism)

Dominion theology is a group of Christian political ideologies that seek to institute a nation governed by Christians based on their personal understandings of biblical law. Extents of rule and ways of achieving governing authority are varied. For example, dominion theology can include theonomy, but does not necessarily involve advocating Mosaic law as the basis of government. The label is applied primarily toward groups of Christians in the United States.

Prominent adherents of these ideologies are otherwise theologically diverse, including Calvinist Christian reconstructionism, Roman Catholic Integralism, Charismatic/Pentecostal Kingdom Now theology, New Apostolic Reformation, and others. Most of the contemporary movements labeled dominion theology arose in the 1970s from religious movements asserting aspects of Christian nationalism.

Some have applied the term dominionist more broadly to the whole Christian right. This usage is controversial. There are concerns from members of these communities that this is a label being used to marginalize Christians from public discussions. Others argue this allegation can be difficult to sympathize with considering the political power already held by these groups and on account of the often verbally blatant intention of these groups to influence the political, social, financial, and cultural spectrums of society for a specific religion, often at the expense of other marginalized groups.

Dystopian

-See Utopian

Ecclesia (or Ekklesia)

-See Christian Church, above

Ecclesiology

[from the Greek ἐκκλησίᾱ, ekklēsiā (Latin ecclesia) meaning “gathering of those summoned” and -λογία, -logia, meaning “words”, “knowledge”, or “logic”]

Ecclesiology is a combining term used in the names of sciences or bodies of knowledge. In Christian theology, ecclesiology is the study of the Christian Church, the origins of Christianity, its relationship to Jesus, its role in salvation, its polity, its discipline, its destiny, and its leadership. Since different ecclesiologies give shape to very different institutions or denominations, there are many subfields such as Catholic ecclesiology, Protestant ecclesiology, and ecumenical ecclesiology.

*In the Greco-Roman world, ecclesia was used to refer to a lawful assembly, or a called legislative body. As early as Pythagoras, the word took on the additional meaning of a community with shared beliefs. This is the meaning taken in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures (the Septuagint), and later adopted by the Christian community to refer to the assembly of believers.

Catholic ecclesiology today has a plurality of models and views, as with all Catholic Theology since the acceptance of scholarly Biblical criticism that began in the early to mid 20th century. This shift is most clearly marked by the encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu in 1943. Avery Robert Cardinal Dulles, S.J. contributed greatly to the use of models in understanding ecclesiology. In his work Models of the Church, he defines five basic models of Church that have been prevalent throughout the history of the Catholic Church. These include models of the Church as institution, as mystical communion, as sacrament, as herald, and as servant.

The ecclesiological model of Church as an Institution holds that the Catholic Church alone is the “one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church”, and is the only Church of divine and apostolic origin. This view of the Church is dogmatically defined Catholic doctrine, and is therefore de fide. In this view, the Catholic Church— composed of all baptized, professing Catholics, both clergy and laity—is the unified, visible society founded by Christ himself, and its hierarchy derives its spiritual authority through the centuries, via apostolic succession of its bishops, most especially through the bishop of Rome (the Pope) whose successorship comes from St. Peter the Apostle, whom Christ gave “the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven”. Thus, the Popes, in the Catholic view, have a God-ordained universal jurisdiction over the whole Church on earth. The Catholic Church is considered Christ’s mystical body, and the universal sacrament of salvation, whereby Christ enables human to receive sanctifying grace.

The model of Church as Mystical Communion draws on two major Biblical images, the first of the “Mystical Body of Christ” (as developed in Paul’s Epistles) and the second of the “People of God.” This image goes beyond the Aristotelian-Scholastic model of “Communitas Perfecta” held in previous centuries. This ecclesiological model draws upon sociology and articulations of two types of social relationships: a formally organized or structured society Gesellschaft) and an informal or interpersonal community (Gemeinschaft). The Catholic theologian Arnold Rademacher maintained that the Church in its inner core is community (Gemeinschaft) and in its outer core society (Gesellschaft). Here, the interpersonal aspect of the Church is given primacy and that the structured Church is the result of a real community of believers. Similarly, Yves Congar argued that the ultimate reality of the Church is a fellowship of persons. This ecclesiology opens itself to ecumenism and was the prevailing model used by the Second Vatican Council in its ecumenical efforts. The Council, using this model, recognized in its document “Lumen gentium“> that the Body of Christ subsists in a visible society governed by the Successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him, although many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside its visible structure.”

From the Eastern Orthodox perspective, the Church is one, even though She is manifested in many places. Eastern Orthodox ecclesiology operates with a plurality in unity and a unity in plurality. For Eastern Orthodoxy there is no ‘either / or’ between the one and the many. No attempt is made, or should be made, to subordinate the many to the one (the Roman Catholic model), nor the one to the many (the Protestant model). It is both canonically and theologically correct to speak of the Church and the churches, and vice versa. Historically, that ecclesiological concept was applied in practice as patriarchal pentarchy, embodied in ecclesiastical unity of five major patriarchal thrones (Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem). There is disagreement between the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Patriarchate of Moscow on the question of separation between ecclesiological and theological primacy and separation of the different ecclesiological levels.

The term Protestant ecclesiology refers to the spectrum of teachings held by the Protestant Reformers concerning the nature and mystery of the Church.

Martin Luther argued that because the Catholic church had “lost sight of the doctrine of grace”, it had “lost its claim to be considered as the authentic Christian church”; this argument was open to the counter-criticism from Catholics that he was thus guilty of schism and a Donatist position, and in both cases therefore opposing central teachings of Augustine of Hippo.

Yet Luther, at least as late as 1519, argued against denominationalism and schism, and the Augsburg Confession of 1530 can be interpreted (e.g. by McGrath 1998) as conciliatory (others, e.g. Rasmussen and Thomassen 2007, marshaling evidence, argue that Augsburg was not conciliatory but clearly impossible for the Roman Catholic Church to accept). “Luther’s early views on the nature of the church reflect his emphasis on the Word of God: the Word of God goes forth conquering, and wherever it conquers and gains true obedience to God is the church”:

“Now, anywhere you hear of see such a word preached, believed, confessed, and acted upon, do not doubt that the true ecclesia sancta catholica, a ‘holy Christian people’ must be there….” [Alister McGrath] “Luther’s understanding of the church is thus functional, rather than historical: what legitimates a church or its office-bearers is not historical continuity with the apostolic church, but theological continuity.”[Gordon Isaac]

John Calvin was among those working, primarily after Martin Luther, in the second generation of Reformers, to develop a more systematic doctrine of the church (i.e. ecclesiology) in the face of the emerging reality of a split with the Catholic church, with the failure of the ecumenical Colloquy of Regensburg in 1541, and the Council of Trent’s condemnation in 1545 of “the leading ideas of Protestantism”. Thus, Calvin’s ecclesiology is progressively more systematic.

The second edition of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion in 1539 holds that “the marks of the true church [are] that the Word of God should be preached, and that the sacraments be rightly administered”. Later, Calvin developed the theory of the fourfold office of pastor, doctor (or teacher), elder, and deacon, possibly owing to the colleagueship with Martin Bucer and his own experience of leadership in church communities.

Calvin also discusses the visible church and the invisible church; the visible church is the community of Christian believers; the invisible church is the fellowship of saints and the company of the elect; both must be honored; “there is only one church, a single entity with Jesus Christ as its head” (McGrath); the visible church will include the good and the evil, a teaching found in the patristic tradition of Augustine and rooted in the divine teaching, recorded in the Gospel according to Matthew, of the Parable of the Tares (Mt 13:24-31); thus, Calvin held that it is “not the quality of its members, but the presence of the authorised means of grace, [that] constitutes a true church” (McGrath).

Calvin was concerned to avoid further fragmentation, i.e. splits among the Evangelical churches: “I am saying that we should not desert a church on account of some minor disagreement, if it upholds sound doctrine over the essentials of piety, and maintains the use of the sacraments established by the Lord.”

There is no single “Radical Reformation Ecclesiology”. A variety of views is expressed among the various “Radical Reformation” participants.

A key “Radical Reformer” was Menno Simons, known as an “Anabaptist”. He wrote: “They verily are not the true congregation of Christ who merely boast of his name. But they are the true congregation of Christ who are truly converted, who are born from above of God, who are of a regenerate mind by the operation of the Holy Spirit through the hearing of the divine Word, and have become the children of God, have entered into obedience to him, and live unblamably in his holy commandments, and according to his holy will with all their days, or from the moment of their call. This was in direct contrast to the hierarchical, sacramental ecclesiology that characterized the incumbent Roman Catholic tradition as well as the new Lutheran and other prominent Protestant movements of the Reformation.

Some other Radical Reformation ecclesiology holds that “the true church [is] in heaven, and no institution of any kind on earth merit[s] the name ‘church of God.’”

Entropy

The first law of thermodynamics is simply a statement of energy conservation. That is, it states that energy can always be accounted for, that the energy of the universe is a constant – it can be transferred between objects and can change form, but the total doesn’t change. But the first law does not preclude things occurring that we know do not occur: A glass of water does not spontaneously separate into ice cubes and warm water even though the energy balance equations used in calorimetry problems would allow it. That is, energy conservation – the first law of thermodynamics – would allow for the possibility that a system in thermal equilibrium could separate into two systems – one at a higher temperature than the other – and that temperature difference could then be used to drive a heat engine to do work. The second law of thermodynamics explains why the universe does not work that way. It articulates the underlying principle that gives the direction of heat flow in any thermal process. The result, of course, fits our everyday experience. The second law states the reason why it is true.

Entropy is an important concept in the branch of physics known as thermodynamics [as it relates to the second law]. The idea of “irreversibility” is central to the understanding of entropy. Everyone has an intuitive understanding of irreversibility. If one watches a movie of everyday life running forward and in reverse, it is easy to distinguish between the two. The movie running in reverse shows impossible things happening – water jumping out of a glass into a pitcher above it, smoke going down a chimney, water in a glass freezing to form ice cubes, crashed cars reassembling themselves, and so on. The intuitive meaning of expressions such as “you can’t unscramble an egg”, or “you can’t take the cream out of the coffee” is that these are irreversible processes. No matter how long you wait, the cream won’t jump out of the coffee into the creamer.

In thermodynamics, one says that the “forward” processes – pouring water from a pitcher, smoke going up a chimney, etc. – are “irreversible”: they cannot happen in reverse. All real physical processes involving systems in everyday life, with many atoms or molecules, are irreversible. For an irreversible process in an isolated system (a system not subject to outside influence), the thermodynamic state variable known as entropy is never decreasing. In everyday life, there may be processes in which the increase of entropy is practically unobservable, almost zero. In these cases, a movie of the process run in reverse will not seem unlikely. For example, in a 1-second video of the collision of two billiard balls, it will be hard to distinguish the forward and the backward case, because the increase of entropy during that time is relatively small. In thermodynamics, one says that this process is practically “reversible”, with an entropy increase that is practically zero. The statement of the fact that the entropy of an isolated system never decreases is known as the second law of thermodynamics.

The second law of thermodynamics can be summarized in many different statements – and has been by many thermodynamicists in the last century and a half. All of the statements are an attempt to put a reason to the things all of us have observed – that when two objects are in thermal contact, heat always goes from the warmer to the cooler and never the other way. This universal result has probably as many explanations as there are physicists trying to explain it – and is still the subject of serious consideration by some of the best theorists. The difficulty does not lie in what the second law says – or how it should be interpreted – but rather in what the fundamental, underlying reason is for why nature behaves in that way.

- Any process either increases the entropy of the universe – or leaves it unchanged. Entropy is constant only in reversible processes which occur in equilibrium. All natural processes are irreversible.

- All natural processes tend toward increasing disorder. And although energy is conserved, its availability is decreased.

- Nature proceeds from the simple to the complex, from the orderly to the disorderly, from low entropy to high entropy.

- The entropy of a system is proportional to the logarithm of the probability of that particular configuration of the system occurring. The more highly ordered the configuration of a system, the less likely it is to occur naturally – hence the lower its entropy.

- In the language of entropy, the Carnot cycle still represents the theoretical maximum efficiency in any cyclic process. That is, maximum efficiency would occur if the entropy of the universe did not increase, hence there would be no loss of availability of doing work. But entropy can only remain constant in a reversible isothermal process. So, again, any heat transfer would have to occur isothermally. Therefore the most efficient cyclic process possible involves only reversible isothermal steps and steps in which no heat is transferred – i.e., adiabatic. And even in this idealized reversible process in which the entropy of the universe was left unchanged, the efficiency of conversion of heat to work is limited by the two temperatures involved in the isothermal steps.

Based on the ideas of Lord Kelvin, Joule, Boltzmann, Carnot, and Clausius, the first and second laws of thermodynamics can now be restated in two profound sentences:

- The total energy of the universe is a constant.

- The total entropy of the universe always increases.

And these two fundamental principles of nature describe how the universe works.

Epistemology

[(/ɪˌpɪstɪˈmɒlədʒi/) from Greek ἐπιστήμη, epistēmē, meaning ‘knowledge’, and λόγος, logos, meaning ‘logical discourse’]

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with the theory of knowledge.

Epistemology studies the nature of knowledge, justification, and the rationality of belief. Much debate in epistemology centers on four areas: (1) the philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and how it relates to such concepts as truth, belief, and justification, (2) various problems of skepticism, (3) the sources and scope of knowledge and justified belief, and (4) the criteria for knowledge and justification. Epistemology addresses such questions as: “What makes justified beliefs justified?”, “What does it mean to say that we know something?”, and fundamentally “How do we know that we know?”

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistemology,

- [See also Schumacher: https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/08/22/schumacher-adaequatio-understanding/]

Eschatology

[ɛskəˈtɒlədʒi]

Eschatology is a part of theology concerned with the final events of history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity. This concept is commonly referred to as the “end of the world” or “end times”.

The word arises from the Greek ἔσχατος eschatos meaning “last” and -logy meaning “the study of”, and was first used in English around 1844. The Oxford English Dictionary defines eschatology as “the part of theology concerned with death, judgment, and the final destiny of the soul and of humankind”.

In the context of mysticism, the phrase refers metaphorically to the end of ordinary reality and reunion with the Divine. In many religions it is taught as an existing future event prophesied in sacred texts or folklore.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eschatology

- See also expanded definitions of “Futurism” and “Inaugurated Eschatology” below

Eternity

Eternity in common parlance is an infinitely long period of time. In classical philosophy, however, eternity is defined as what exists outside time while sempiternity is the concept that corresponds to the colloquial definition of eternity.

Eternity is an important concept in many religions, where the god or gods are said to endure eternally. Some, such as Aristotle, would say the same about the natural cosmos in regard to both past and future eternal duration, and like the eternal Platonic forms, immutability was considered essential.

Evolution

The English noun evolution (from Latin ēvolūtiō “unfolding, unrolling”) refers to any kind of accumulation of change, or gradual directional change.

While the term primarily refers to biological evolution in current parlance, there are various types of chemical evolution, and it is also found in economics, historical linguistics, and many other technical fields where systems develop or change gradually over time, e.g. stellar evolution, cultural evolution, the evolution of an idea, metaphysical evolution, spiritual evolution, etc.

The English term prior to the late 19th century was confined to referring to goal-directed, pre-programmed processes such as embryological development. A pre-programmed task, as in a military maneuver, using this definition, may be termed an “evolution.”

The term evolution (from its literal meaning of “unfolding” of something into its true or explicit form) carries a connotation of gradual improvement or directionality from a beginning to an end point. This contrasts with the more general development, which can indicate change in any direction, or revolution, which implies recurring, periodic change. The term biological devolution is coined as an antonym to evolution, indicating such degeneration or decrease in quality or complexity.

Six Principal Meanings of Evolution in Biology Textbooks

1. Evolution as change over time: history of nature; any sequence of events in nature. Nature has a history; it is not static. Natural sciences deal with evolution in its first sense – change over time in the national natural world – when they seek to reconstruct series of past events to tell the story of nature’s history.

2. Evolution as gene frequency change, AKA microevolution. Population geneticists study changes in the frequencies of alleles in gene pools. This very specific sense of evolution, though not without theoretical significance, is closely tied to a large collection of precise observations. For the geneticist, gene frequency change is “evolution in action.”

3. Evolution as limited common descent: the idea that particular groups of organisms have descended from a common ancestor. Evolution defined as “limited common descent“ designates the scientifically uncontroversial idea that many different varieties of similar organisms within different species, genera, or even families are related by common ancestry. Note that it is possible for some scientists to accept evolution when defined in this sense without necessarily accepting evolution defined as universal common descent – that is, the idea that all organisms are related by common ancestry.

4. Evolution as a mechanism that produces limited change or descent with modification, chiefly natural selection acting on random variations are mutations. The term evolution also refers to the mechanism that produces the morphological change implied by limited common descent or descent with modification through successive generations. Almost all biologists would accept that the variation/selection mechanism can explain relatively minor variations among groups of organisms (meaning #4), even if some of those biologists question the sufficiency of the mechanism (meaning #6) as an explanation for the origin of the major morphologic innovations in the history of life.

5. Evolution as universal common descent, AKA Darwinism: the idea that all organisms have descended from a single common ancestor. Many biologists commonly use the term evolution to refer to the idea that all organisms are related by common ancestry from a single living organism. Darwin represented the theory of universal common descent or universal “descent with modification“ with a “branching tree“ diagram, which showed all present life forms of as having emerged gradually over time from one or very few original common ancestors. Darwin’s theory of biological history is often referred to as a monophyletic view because it portrays all organisms as ultimately related to a single family. Although Darwin’s monophyletic view of life’s history has reigned as the dominant theory of the history of life during most of the twentieth century, a number of biologists now question that view on evidential grounds. These scientists now see the present diversity and disparity of organisms as having originated from many separate ancestral forms and lines of descent. Those favoring a so-called polyphyletic or multiple separate origins review of life’s history now cite evidence from paleontology, embryology, biochemistry, and molecular biology in support of their view.

6. Evolution as the “Blind Watchmaker“ Thesis, AKA neo-Darwinism. The “blind watchmaker“ thesis, to appropriate Richard Dawkins’s clever term, stands for the Darwinian idea that all new living forms arose as the product of unguided, purposeless, material mechanisms, chiefly natural selection acting on random variation or mutations. As Dawkins summarizes the blind watchmaker thesis: “Natural selection, the blind, unconscious, automatic process which Darwin discovered and which we now know is the explanation for the existence and apparently purposeful form of all life, has no purpose in mind. It has no mind and no mind’s eye.”

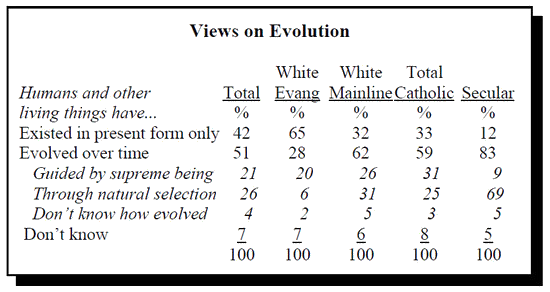

Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life Research Center United States Survey Summer 2006

Evolve

1. To develop gradually

- ‘The company has evolved into a major chemical manufacturer.’

- ‘The Gothic style evolved from the Romanesque.’

- ‘Each school must evolve its own way of working.’

Synonyms: develop, progress, make progress, advance, move forward, make headway, mature, grow, open out, unfold, unroll, expand, enlarge, spread, extend

1.1 (with reference to an organism or biological feature) develop over successive generations as a result of natural selection.

‘The domestic dog is thought to have evolved from the wolf’

2. To give off gas or heat (chemistry)

- ‘The energy evolved during this chemical change is transferred to water’

Synonyms: emit, yield, give off, discharge, release, produce

Origin: Early 17th century (in the general sense ‘make more complex, develop’): from Latin evolvere, from e- (variant of ex-) ‘out of’ + volvere ‘to roll’.

- See link below for many more example sentences of each usage. Also consider similar words “revolve” and “revolution”.

- On a more humorous note, let the popular colloquial proverb “What goes around comes around” roll around in your mind…

Faith

Dictionary definition:

- complete trust or confidence in someone or something. “this restores one’s faith in politicians”

Synonyms: trust, belief, confidence, conviction… - strong belief in God or in the doctrines of a religion, based on spiritual apprehension rather than proof.

Synonyms: religion, church, sect, denomination, (religious) persuasion, (religious) belief, ideology, creed, teaching, doctrine

“she gave her life for her faith” - a system of religious belief. plural noun: faiths “the Christian faith”

- a strongly held belief or theory. “the faith that life will expand until it fills the universe”

Wikipedia:

In the context of religion, one can define faith as confidence or trust in a particular system of religious belief, within which faith may equate to confidence based on some perceived degree of warrant, in contrast to a definition of faith as being belief without evidence.

- Etymology:

The English word faith is thought to date from 1200–1250, from the Middle English feith, via Anglo-French <fed, Old French feid, feit from Latin fidem, accusative of fidēs (trust), akin to fīdere (to trust).

(Note: The above article is about religious belief. For trust in people or other things, see article below)

In a social context, trust has several connotations. Definitions of trust typically refer to a situation characterized by the following aspects: One party (trustor) is willing to rely on the actions of another party (trustee); the situation is directed to the future. In addition, the trustor (voluntarily or forcedly) abandons control over the actions performed by the trustee. As a consequence, the trustor is uncertain about the outcome of the other’s actions; they can only develop and evaluate expectations. The uncertainty involves the risk of failure or harm to the trustor if the trustee will not behave as desired.

Free Will

Free will is the ability to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of responsibility, praise, guilt, sin, and other judgments which apply only to actions that are freely chosen. It is also connected with the concepts of advice, persuasion, deliberation, and prohibition. Traditionally, only actions that are freely willed are seen as deserving credit or blame. There are numerous different concerns about threats to the possibility of free will, varying by how exactly it is conceived, which is a matter of some debate.

Some conceive free will to be the capacity to make choices in which the outcome has not been determined by past events. Determinism suggests that only one course of events is possible, which is inconsistent with the existence of free will thus conceived. This problem has been identified in ancient Greek philosophy and remains a major focus of philosophical debate. This view that conceives free will to be incompatible with determinism is called incompatibilism and encompasses both metaphysical libertarianism, the claim that determinism is false and thus free will is at least possible, and hard determinism, the claim that determinism is true and thus free will is not possible. It also encompasses hard incompatibilism, which holds not only determinism but also its negation to be incompatible with free will and thus free will to be impossible whatever the case may be regarding determinism.

The underlying questions are whether we have control over our actions, and if so, what sort of control, and to what extent. These questions predate the early Greek stoics (for example, Chrysippus), and some modern philosophers lament the lack of progress over all these centuries. On one hand, humans have a strong sense of freedom, which leads us to believe that we have free will. On the other hand, an intuitive feeling of free will could be mistaken.

Futurism

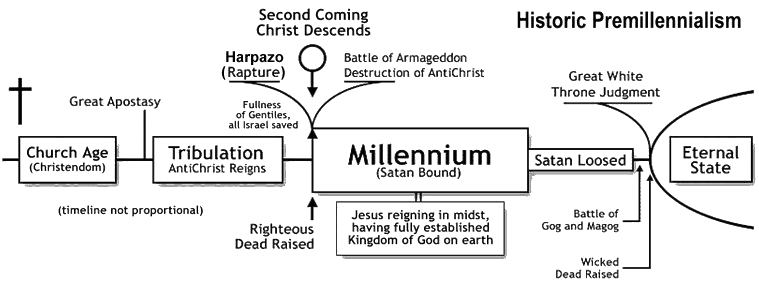

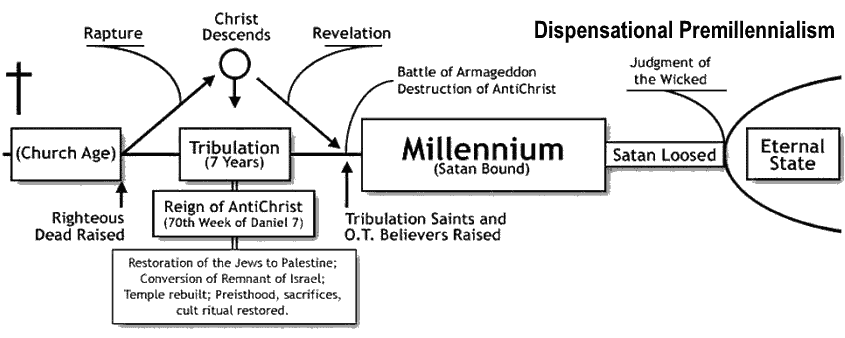

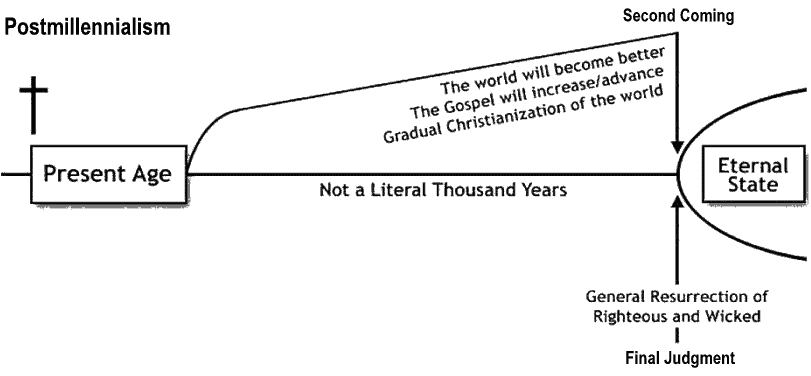

[See Millennialism, below] Futurist interpretations differ in two primary ways having to do with the second coming (return) of Christ and the timing of 1) the start of Christ’s millennial reign with vis-a-vis the final tribulation, and 2) the “snatching up” (or “rapture”) of believers to meet Christ in the air.

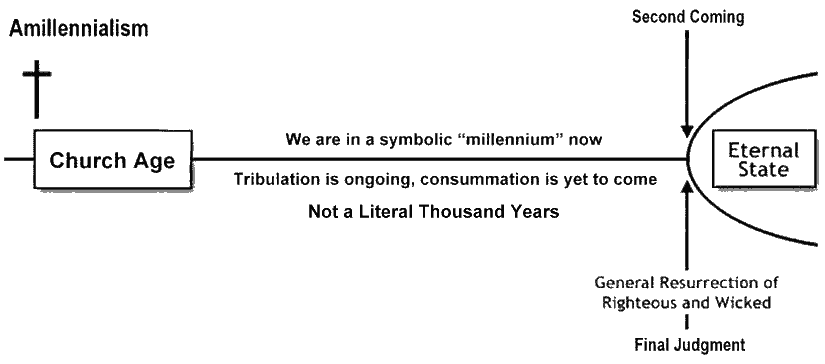

- With respect to the first (Christ’s return), there are three basic views: amillennial, premillennial, and postmillennial with premillennial being further divided into two views, historic and dispensational.

- With respect to the second (the rapture of the church), there are three divisions pre-trib, mid-trib, and post-trib.

Clearly, there are a number of possible permutations of these differing eschatological interpretations. See Millennial Views below for more particulars about each position.

Through prayer, ongoing study of the Scriptures, and a sense of wisdom gathered in the course of decades of human experience in God’s ways, I have been led to believe personally in an inaugurated futuristic eschatology characterized by historical post-tribulational premillennialism. What a mouthful! In other words, I believe that Jesus came, inaugurated the onset of the kingdom of God on earth and proclaimed it as good news, and is operating in the world today through his Holy Spirit to win believers to the kingdom and to inaugurate as much of it as can be done prior to his second coming or return in the future.

Pre-tribulation reading of Revelations by Ron Rhodes:

- https://www.christianbook.com/chronological-complete-overview-understanding-bible-prophecy/ron-rhodes/9780736937788/pd/937788?event=AFF&p=1011693&

- https://www.gotquestions.org/end-times-timeline.html

Great Awakenings

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The movement began around 1790, gained momentum by 1800 and, after 1820, membership rose rapidly among Baptist and Methodist congregations whose preachers led the movement. It was past its peak by the late 1850s. The Second Great Awakening reflected Romanticism characterized by enthusiasm, emotion, and an appeal to the supernatural. It rejected the skeptical rationalism and deism of the Enlightenment.

The revivals enrolled millions of new members in existing evangelical denominations and led to the formation of new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age. The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements designed to remedy the evils of society before the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

Historians named the Second Great Awakening in the context of the First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s and of the Third Great Awakening of the late 1850s to early 1900s. These revivals were part of a much larger Romantic religious movement that was sweeping across Europe at the time, mainly throughout England, Scotland, and Germany.

Hermeneutics

[hɜːrməˈnjuːtɪks]

Hermeneutics is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts.

Modern hermeneutics includes both verbal and non-verbal communication as well as semiotics, presuppositions, and pre-understandings. Hermeneutics has been broadly applied in the humanities, especially in law, history and theology.

Hermeneutics was initially applied to the interpretation, or exegesis, of scripture, and has been later broadened to questions of general interpretation. The terms “hermeneutics” and “exegesis” are sometimes used interchangeably. Hermeneutics is a wider discipline which includes written, verbal, and non-verbal communication. Exegesis focuses primarily upon the word and grammar of texts.

Hermeneutic, as a singular noun, refers to some particular method of interpretation (see, in contrast, double hermeneutic).

Holy

Definition

- exalted or worthy of complete devotion as one perfect in goodness and righteousness

- DIVINE / “for the Lord our God is holy” — Psalms 99:9 (King James Version)

- devoted entirely to the deity or the work of the deity, as in a holy temple or holy prophets

- a: having a divine quality, as in holy love

b: venerated as or as if sacred, as in holy scripture or a holy relic - used as an intensive, as in “this is a holy mess” or “he was a holy terror when he drank”

—often used in combination as a mild oath as in “holy smoke”

Synonyms

divine, hallowed, humble, pure, revered, righteous, spiritual, sublime, believing, clean, devotional, faithful, good, innocent, moral, perfect, upright, angelic, blessed, chaste, consecrated, dedicated, devoted, devout, faultless, glorified, god-fearing, godlike, godly, immaculate, just, messianic, pietistic, pious, prayerful, reverent, sacrosanct, sainted, saintlike, saintly, sanctified, seraphic, spotless, uncorrupt, undefiled, untainted, unworldly, venerable, venerated, virtuous

I Ching

The I Ching or Yi Jing (Chinese: 易經; pinyin: Yìjīng; Mandarin pronunciation: [î tɕíŋ]. The Yi means “changes” and the Jing means “great book” or “classic”), also known as Classic of Changes or Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text and the oldest of the Chinese classics. Possessing a history of more than two and a half millennia of commentary and interpretation, the I Ching is an influential text read throughout the world, providing inspiration to the worlds of religion, psychoanalysis, literature, and art. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), over the course of the Warring States period and early imperial period (500–200 BC) it was transformed into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the “Ten Wings”. After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

The I Ching uses a type of divination called cleromancy, which produces apparently random numbers. Six numbers between 6 and 9 are turned into a hexagram, which can then be looked up in the I Ching book, arranged in an order known as the King Wen sequence. The interpretation of the readings found in the I Ching is a matter of centuries of debate, and many commentators have used the book symbolically, often to provide guidance for moral decision making as informed by Taoism and Confucianism. The hexagrams themselves have often acquired cosmological significance and paralleled with many other traditional names for the processes of change such as yin and yang and Wu Xing.

The divination text: Zhou yi

The core of the I Ching is a Western Zhou divination text called the Changes of Zhou (周易 Zhōu yì). Various modern scholars suggest dates ranging between the 10th and 4th centuries BC for the assembly of the text in approximately its current form. Based on a comparison of the language of the Zhou yi with dated bronze inscriptions, the American sinologist Edward Shaughnessy dated its compilation in its current form to the early decades of the reign of King Xuan of Zhou, in the last quarter of the 9th century BC. A copy of the text in the Shanghai Museum corpus of bamboo and wooden slips (recovered in 1994) shows that the Zhou yi was used throughout all levels of Chinese society in its current form by 300 BC, but still contained small variations as late as the Warring States period. It is possible that other divination systems existed at this time; the Rites of Zhou name two other such systems, the Lianshan and the Guicang.

Hexagrams

In the canonical I Ching, the hexagrams are arranged in an order dubbed the King Wen sequence after King Wen of Zhou, who founded the Zhou dynasty and supposedly reformed the method of interpretation. The sequence generally pairs hexagrams with their upside-down equivalents, although in eight cases hexagrams are paired with their inversion. Another order, found at Mawangdui in 1973, arranges the hexagrams into eight groups sharing the same upper trigram. But the oldest known manuscript, found in 1987 and now held by the Shanghai Library, was almost certainly arranged in the King Wen sequence, and it has even been proposed that a pottery paddle from the Western Zhou period contains four hexagrams in the King Wen sequence. Whichever of these arrangements is older, it is not evident that the order of the hexagrams was of interest to the original authors of the Zhou yi. The assignment of numbers, binary or decimal, to specific hexagrams is a modern invention. The following table numbers the first six of the full array of 64 hexagrams in King Wen order:

| 1 乾 (qián) |

2 坤 (kūn) |

3 屯 (zhūn) |

4 蒙 (méng) |

5 需 (xū) |

6 訟 (sòng) |

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Ching

- Not to be confused with the Tao Te Ching (see below), a separate book with which it is often coupled.

- [Note: the author of this website was mistakenly drawn to use the I Ching and its hexagram divination method extensively during the development of his attempts in the early 1970s to reform the NYS prison medical system at Attica, as described in the first 3 Books of his Hydra manuscript.]

Inaugurated eschatology

Inaugurated eschatology postulates that the kingdom of God, as prophesied in Isaiah 35, was publicly inaugurated and proclaimed at the first coming of Jesus and is now here, although it will not be fully consummated until His second coming. Inaugurated eschatology is also sometimes referred to as a “partially realized eschatology” and is associated with the “already but not yet” concept.

This theological concept of “already” and “not yet” was proposed by Princeton theologian Gerhardus Vos early in the 20th century, who believed that we live in the present age, the ‘now’, and await the ‘age to come’. Kingdom theology was more fully examined in the 1950s by George Eldon Ladd, then a professor of biblical theology at Fuller Theological Seminary. He argued that there are two true meanings to the kingdom of God: Firstly, he proposed that the kingdom of God is God’s authority and right to rule. Secondly, he argued that it also refers to the realm in which God exercises his authority, which is described in scripture both as a kingdom that is presently entered into and as one which will be entered in the future. He concluded that the kingdom of God is both present and future.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inaugurated_eschatology

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_theology

The book of Revelation has always presented the interpreter with challenges. The book is steeped in vivid imagery and symbolism which people have interpreted differently depending on their preconceptions of the book as a whole. There are four main interpretive approaches to the book of Revelation: 1) preterist (which sees all or most of the events in Revelation as having already occurred by the end of the 1st century); 2) historicist (which sees Revelation as a survey of church history from apostolic times to the present); 3) idealist (which sees Revelation as a depiction of the struggle between good and evil); 4) futurist (which sees Revelation as prophecy of events to come). Of the four, only the futurist approach interprets Revelation in the same grammatical-historical method as the rest of Scripture. It is also a better fit with Revelation’s own claim to be prophecy (Revelation 1:3; 22:7, 10, 18, 19).

Intelligent Design

Intelligent design refers to a scientific research program as well as a community of scientists, philosophers and other scholars who seek evidence of design in nature. The theory of intelligent design holds that certain features of the universe and of living things are best explained by an intelligent cause, not an undirected process such as natural selection. Through the study and analysis of a system’s components, a design theorist is able to determine whether various natural structures are the product of chance, natural law, intelligent design, or some combination thereof. Such research is conducted by observing the types of information produced when intelligent agents act.

Is Intelligent Design Creationism?

No. The theory of intelligent design is simply an effort to empirically detect whether the “apparent design” in nature acknowledged by virtually all biologists is genuine design (the product of an intelligent cause) or is simply the product of an undirected process such as natural selection acting on random variations.

Is Intelligent Design a Scientific Theory?

Yes. The scientific method is commonly described as a four-step process involving observations, hypothesis, experiments, and conclusion. Intelligent design begins with the observation that intelligent agents produce complex and specified information (CSI). Design theorists hypothesize that if a natural object was designed, it will contain high levels of CSI. Scientists then perform experimental tests upon natural objects to determine if they contain complex and specified information.

Is intelligent design theory incompatible with evolution?

It depends on what one means by the word “evolution.” If one simply means “change over time,” or even that living things are related by common ancestry, then there is no inherent conflict between evolutionary theory and intelligent design theory. However, the dominant theory of evolution today is neo-Darwinism, which contends that evolution is driven by natural selection acting on random mutations, an unpredictable and purposeless process that “has no discernable direction or goal, including survival of a species.” (NABT Statement on Teaching Evolution). It is this specific claim made by neo-Darwinism that intelligent design theory directly challenges.

Mahdi