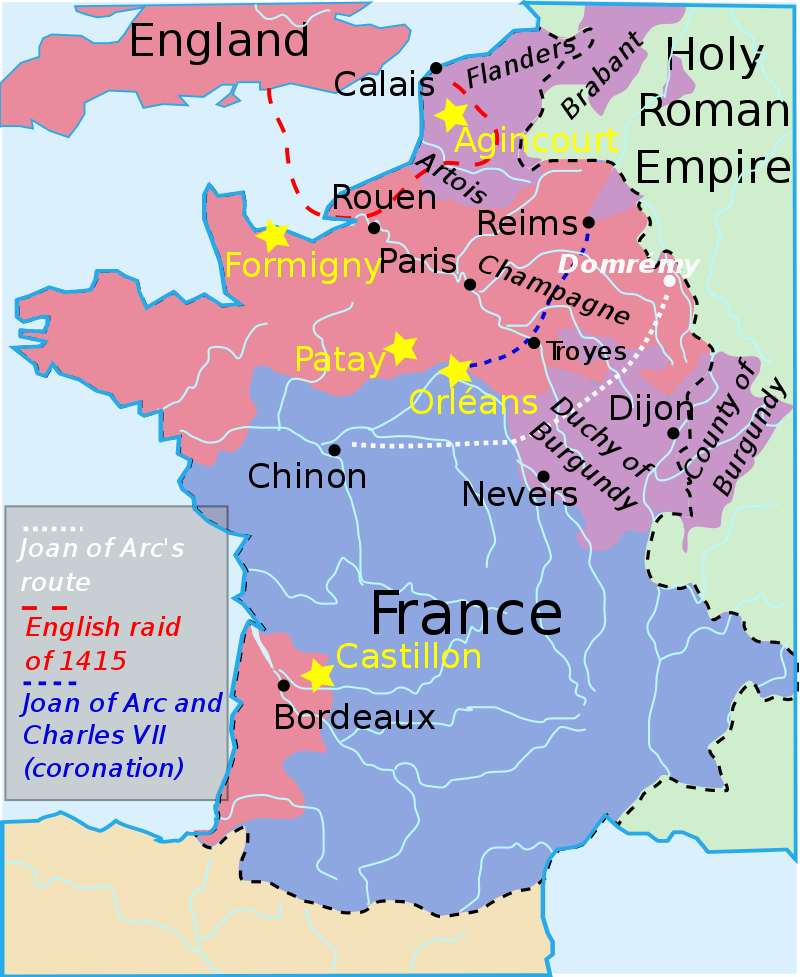

The Hundred Years’ War, 1337-1453

The Hundred Years’ War was an intermittent but ongoing conflict between five generations of English and French rulers over who would rule the Kingdom of France. The war was noted for its length, political and religious complexity, extensive allies on both sides, and the rise and fall of chivalry, with the end result that both countries developed fiercely defended national identities.

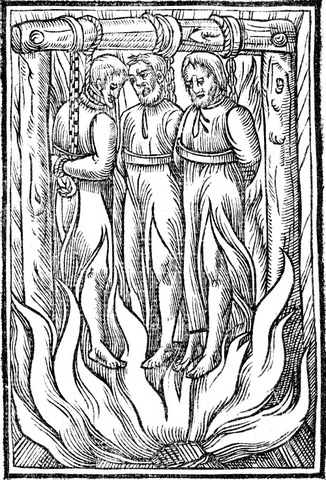

Perhaps the most famous battle was fought during the Siege of Orleans in 1428-29 when a young French peasant girl named Joan of Arc had a spiritual experience that caused her to lead the French forces to victory. She was arrested and turned over to the English after the battle, where she was put to trial on fabricated charges of “heresy” for cross-dressing and burned at the stake in 1431. A revival of faith and French nationalism resulted that turned the tide against the English.

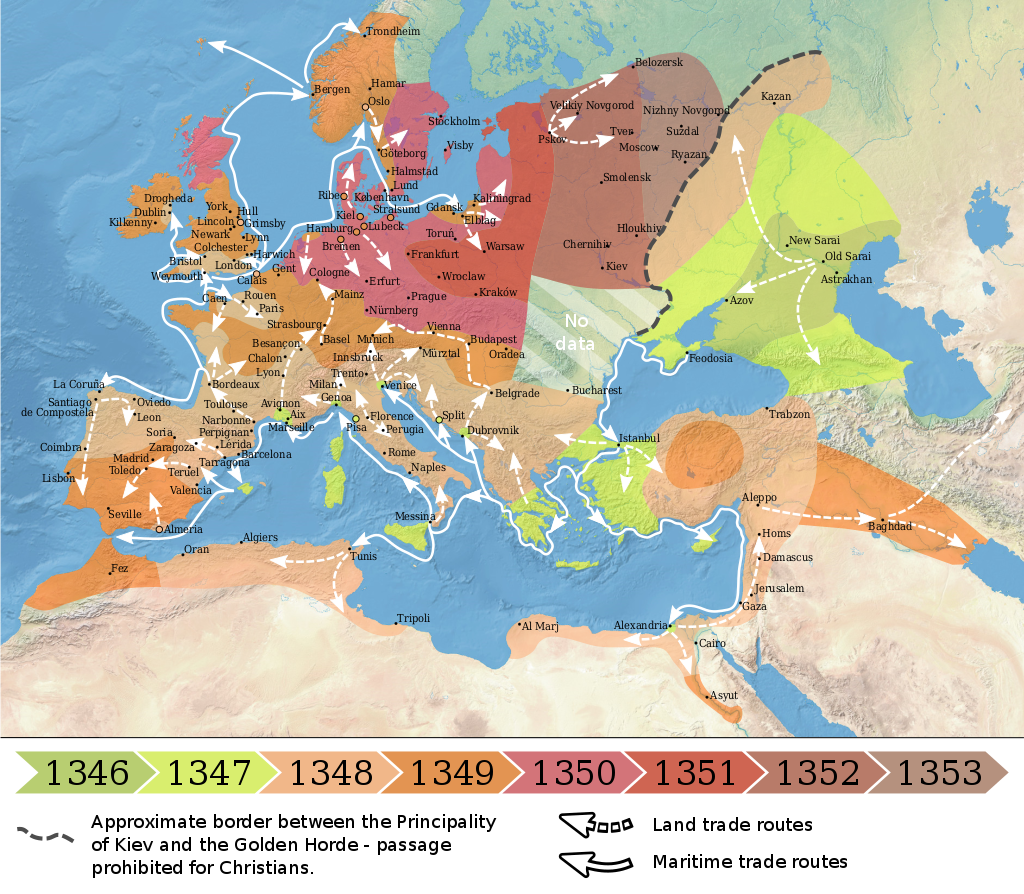

The Black Plague, 1346-1353

In the midst of the Hundred Year’s War the world experienced a second pandemic of the Bubonic Plague, a deadly disease spread by flea bites that had ravaged the Eastern Roman Empire in 541–542 AD, killing 25-50 million people before subsiding. This time the plague apparently traveled along the Silk Road from the Orient and broke out in Eastern Europe. By the time the Black Death, as it came to be known, had run its course the continent of Eurasia had been ravaged, leaving between 75 and 200 million people dead.

Casualties were epic with the overall mortality in Europe as a whole running close to 50% of the population. In territories along the Mediterranean, however, it has been estimated that the toll was closer to 75% with more northern areas in England and Germany staying around 25%.

The resulting social, religious, and economic chaos was devastating.

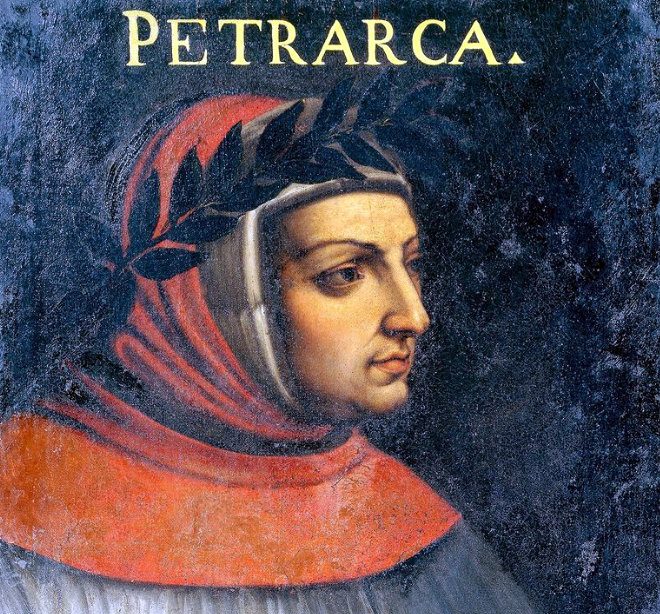

Foreshadowings of the Renaissance

In the Late Middle Ages Italian scholars in Florence began turning their interests to recovering and studying ancient Latin and Greek works of government, history, and literature, while prior to that time they had focused almost entirely on studying Greek and Arabic works of mathematics, science, and philosophy.

When the Renaissance (“revival of interest”) is studied closely, many of the classical ideas that were revived about scholarship, antiquity, and the arts can be found in late 13th-century Florence, especially in the writings of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Petrarch (1304–1374), as well as the paintings of Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337) and a growing throng of others.

As time progressed the recently recovered and expanded humanistic perspective that became characteristic of the Renaissance began to spread throughout the western world, coming to full bloom in the early 16th century as we will see when we look more closely at the Modern Age.

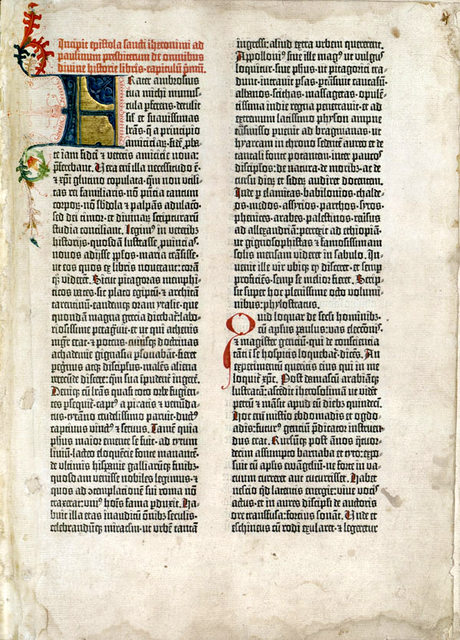

Gutenberg’s printing press and Bible

In Renaissance Europe, the arrival of mechanical movable type printing press pioneered in 1439 by Johannes Gutenberg introduced an era of mass communication which permanently altered the structure of society. Gutenberg was an early Renaissance German metal-smith, inventor, printer, and publisher who combined several elements of printing together – movable type assembled in adjustable molds, oil-based ink, and a screw pressing system – into one process that permitted the relatively affordable and rapid (for the times) duplication and dissemination of printed material. After using the press on several smaller works, Gutenberg became well-known with the printing of his spectacular “Gutenberg Bible” containing the full canon of both Old and New Testaments in an illuminated Vulgate edition based primarily on Jerome’s 4th century Latin translation. As described by Wikipedia:

The relatively unrestricted circulation of information – including revolutionary ideas – transcended borders, captured the masses in the Reformation and threatened the power of political and religious authorities; the sharp increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the literate elite on education and learning and bolstered the emerging middle class. Across Europe, the increasing cultural self-awareness of its people led to the rise of proto-nationalism, accelerated by the flowering of the European vernacular languages to the detriment of Latin’s status as lingua franca.

Savonarola in Florence

To paraphrase Bob Dylan, “times they were a-changin'” in the western world, especially in Italy and even more specifically in Florence. The place that had found itself near the epicenter of the western Roman Empire which contained the seat of the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire was undergoing a profound cultural shift under the oversight of the adventuresome Medici family. Renaissance spirituality was rapidly guiding religion, philosophy, goals, and ideals into more worldly and often licentious pursuits. New frontiers and ways of living were being sought in all directions. A young Florentine man named Girolamo Savonarola became convinced that the world was accelerating in a perilously wrong direction from that called for by the God of the universe, and in 1475 he joined a religious order of monks and wrote to his father to explain why:

The reason why I entered into a religious order is this: first, the great misery of the world, the wickedness of men, the rapes, the adulteries, the thefts, the pride, the idolatry, the vile curses, for the world has come to such a state that one can no longer find anyone who does good; so much so that many times every day I would sing this verse with tears in my eyes: Alas, flee from cruel lands, flee from the shores of the greedy. I did this because I could not stand the great wickedness of the blind people of Italy, especially when I saw that virtue had been completely cast down and vice raised up.

Read the synopsis below of what happened when Savonarola’s ministry matured and then click here to read in greater detail about the remarkable story of his life and its impact.

1492 Revival “John the Baptist of the Reformation”

As the years of training, studying, and teaching went by, Savonarola felt compelled under the conviction of the Holy Spirit to preach a pure Gospel of repentance, forgiveness of sins, and salvation from eternal wrath, and embarked on an itinerant ministry that touched many lives. The same year that Columbus set sail looking for a new trade route to the Orient, Savonarola had a vision In which he saw a warning in Latin that read Ecce gladius Domini super terram, cito et velociter (“Behold the sword of the Lord will descend suddenly and quickly upon the earth”). He envisioned terrible tribulations to come and began preaching prophetically with great passion. Revival broke out in Florence, and the city underwent dramatic changes in personal and social behavior as well as in governance (the ruling Medicis were expelled and replaced by a popular republic). The relationship between Florence and Savonarola and the organized Church in Rome became increasingly strained.

Pope Alexander VI began to question his motives and methods and excommunicated him on May 13, 1497, at which time Savonarola completed his spiritual masterpiece, the Triumph of the Cross. During the year that followed, Florence erupted in divisive social turmoil, leading to his arrest, trial by torture, and condemnation to death by hanging and immolation. On May 23, 1498, Savonarola and two associate friars were publicly executed. Florence continued many of the personal and community reforms that had been inspired by his preaching and witness until the Medicis returned and resumed power in 1512. The cultural stage was being set for Martin Luther.

Columbus comes to America

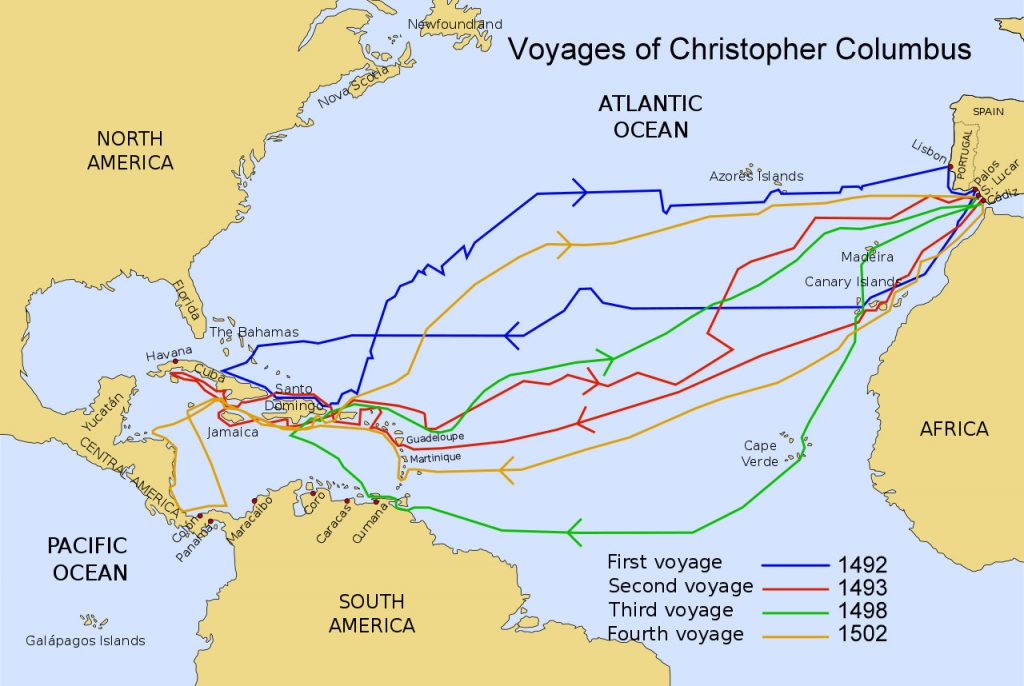

Most of us grew up being taught that Christopher Columbus “sailed the ocean blue in 1492” and “discovered America” in a way that only a gifted explorer could do. Since then a lot has been said about the fact that the “new world” had been populated by Native Americans for millennia prior to the arrival of Columbus and that he brought a lot of European misery with him.

We’ve also noted that the Viking, Lief Erikson, preceded Columbus by “discovering” North America about 500 years earlier. It can be argued that Columbus was more supported by his Spanish Catholic sponsors, making four epic voyages with multiple ships, and that his arrival had a much greater impact on world history. At any rate, reports of his findings soon got out, perhaps spread by Gutenberg’s new printing press and the European lust for commerce, conquest and gold, and the rest is history.

Navigation Notes

Look below and you’ll notice Up and Down buttons in the middle. Using these buttons you can navigate directly through our timelines. For each timeline we will take a detailed tour using the middle buttons to investigate historical events and people noted in bold red on the current chart (7) and outlined in our Middle Ages discussion. Our tour will now bring us to the Modern Age and the dramatic changes in the world leading up to where we are now.